Source

Source: REGIERUNGonline/Bienert

In 1988, journalist Lea Rosh proposed that a memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe be erected on the former grounds of the Gestapo in the Kreuzberg neighborhood of Berlin. Together with historian Eberhard Jäckel, she formed a citizens’ initiative to lobby for the building of a “memorial as a visible acknowledgment of what happened in the past.” The idea met with significant public support, not least from prominent figures like Willy Brandt and Günter Grass. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dismantling of the border between East and West Berlin in 1989/90, the landscape of Berlin changed significantly. In response, the “Association for the Promotion of the Establishment of a Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe” (the group that had grown out of the citizens’ initiative) suggested that the memorial be built in the very heart of Berlin – near the Brandenburg Gate on the grounds of the former Ministerial Gardens. In April 1992, Chancellor Helmut Kohl expressed his support for the plan and declared that the government was ready to allocate a portion of the site for the memorial. Two architectural competitions for the design of the memorial were held in the mid-1990s. On June 25, 1999, after a long debate, the German Bundestag decided that the memorial would be built according to plans by the American architect Peter Eisenman. The Bundestag also decided that an underground information center would be built as well. The center was envisioned as a supplement to the museum, a place where visitors could learn concrete facts about the victims commemorated above. Construction on the project began in April 2003 and ended on December 15, 2004. The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe was inaugurated on May 10, 2005, almost exactly sixty years after the end of the war in Europe.

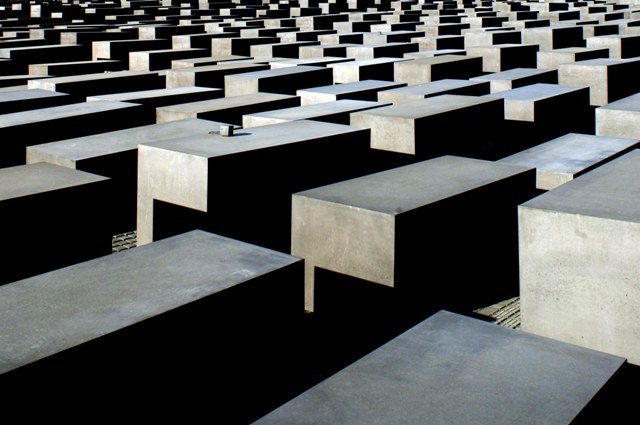

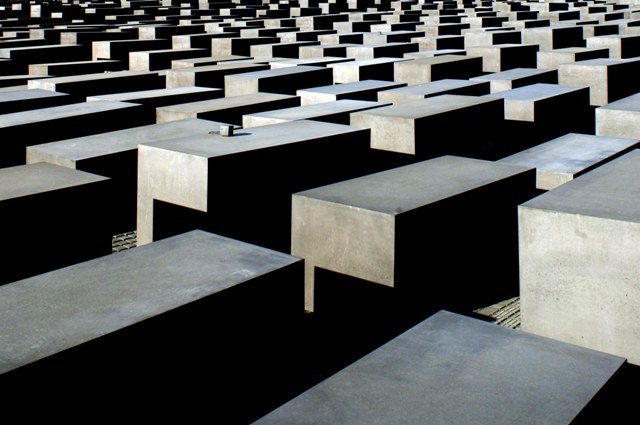

The monument occupies about 19,000 square meters of space; it consists of 2,700 concrete stelae (or pillars) of varying heights and shapes. The dark gray stelae are organized in a grid pattern and separated by paths of uneven cobblestones. The ground underneath them undulates gently. The memorial is accessible on all sides, and no clear dividing line separates the site from the rest of the city. As architectural critic Nicolai Ouroussoff commented, the grid “can be read as both an extension of the streets that surround the site and an unnerving evocation of the rigid discipline and bureaucratic order that kept the killing machine grinding along.” Like others, he reads the stelae as a reference to tombstones. The memorial, which includes no plaques, inscriptions, or symbols, has been criticized by some as too abstract. Others praise the memorial for its complex, thought-provoking, and even unsettling ambiguity.

Source: REGIERUNGonline/Bienert