Abstract

The Berlin Conference of 1884–85 marked the climax of the European

competition for territory in Africa. The “scramble for Africa” had led

to conflict among European powers, particularly between the British and

French in West Africa, the Portuguese and British in East Africa, and

the French and Belgians (under King Leopold II) in the Congo. Such

rivalry impelled Bismarck in late 1884 to convene a meeting of European

powers in Berlin. Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, and King Leopold

II negotiated their claims to African territory, which were then

formalized and mapped. Long before 1884, the representatives of Europe’s

colonial powers had been using the rhetoric of a “civilizing mission” to

legitimate their African claims.

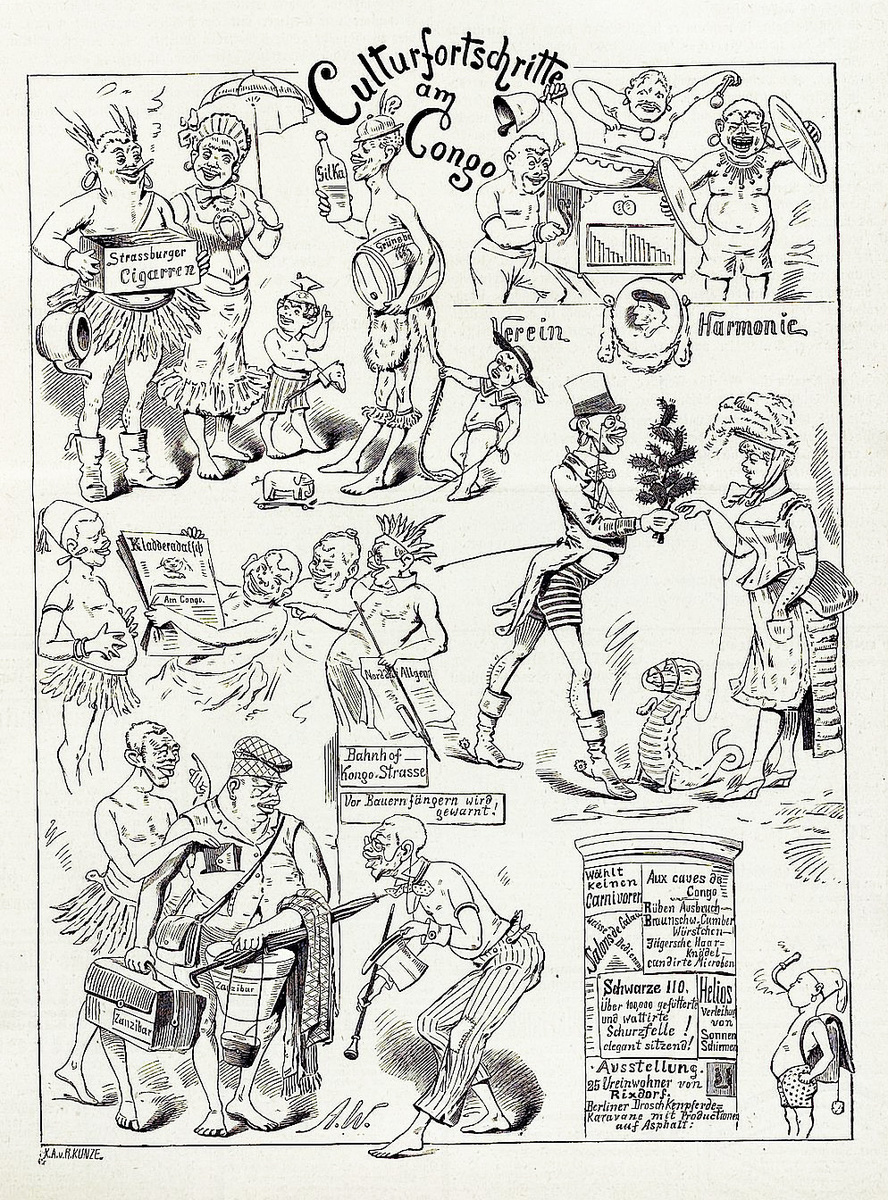

In this cartoon, the satirical journal

Kladderadatsch mocks the “civilizing

mission” argument by suggesting that colonial subjects were not capable

of being “civilized” at all. The cartoon both draws on and reproduces

the trope of the Hosenneger (the

“pants-wearing Negro”)—a colonial subject who aspires to be civilized

but, because of fundamental inferiority, can only fall short. The

subject’s inability to understand European fashions was a central

feature of this trope. In this cartoon, we see a representative range of

everyday German habits transplanted into the Congo: hilarity ensues when

the Africans try to imitate Europeans. A gentleman (middle right),

wearing top hat and ridiculous striped trousers, presents a cactus to

the object of his affection; she wears women’s petticoats and walks her

crocodile on a leash. Three half-naked men at top right, rather than

playing classical instruments or singing in harmony, clash cymbals and

bang on drums in what appears to be a riotous performance. There is a

hint of criticism of colonizing practices in the cigars and alcohol

being exported to the Africans (at top left), as well as a hint of

colonial anxiety in the advertising column (bottom right): with an

absurd election cry (“Don’t vote for carnivores” – “Wählt keinen

Carnivoren”), the column presents the possibility of up-ended

hierarchies wherein a so-called

Völkerschau brings twenty-five Berlin

workers (Rixdorfers) for Africans to ogle, and the

Salons de Calau advertises that it

employs white waiters. The figures are caricatured in ways that presume

and present racial inferiority, thereby reinforcing notions of absolute

difference between colonizer and colonized that were still in flux at

this time. In this sense, the group of Africans reading

Kladderadatsch, in which this cartoon

appeared, are symbolically important: their grotesque features and lack

of clothing highlight just how far removed they are from Germans reading

the same publication.