Abstract

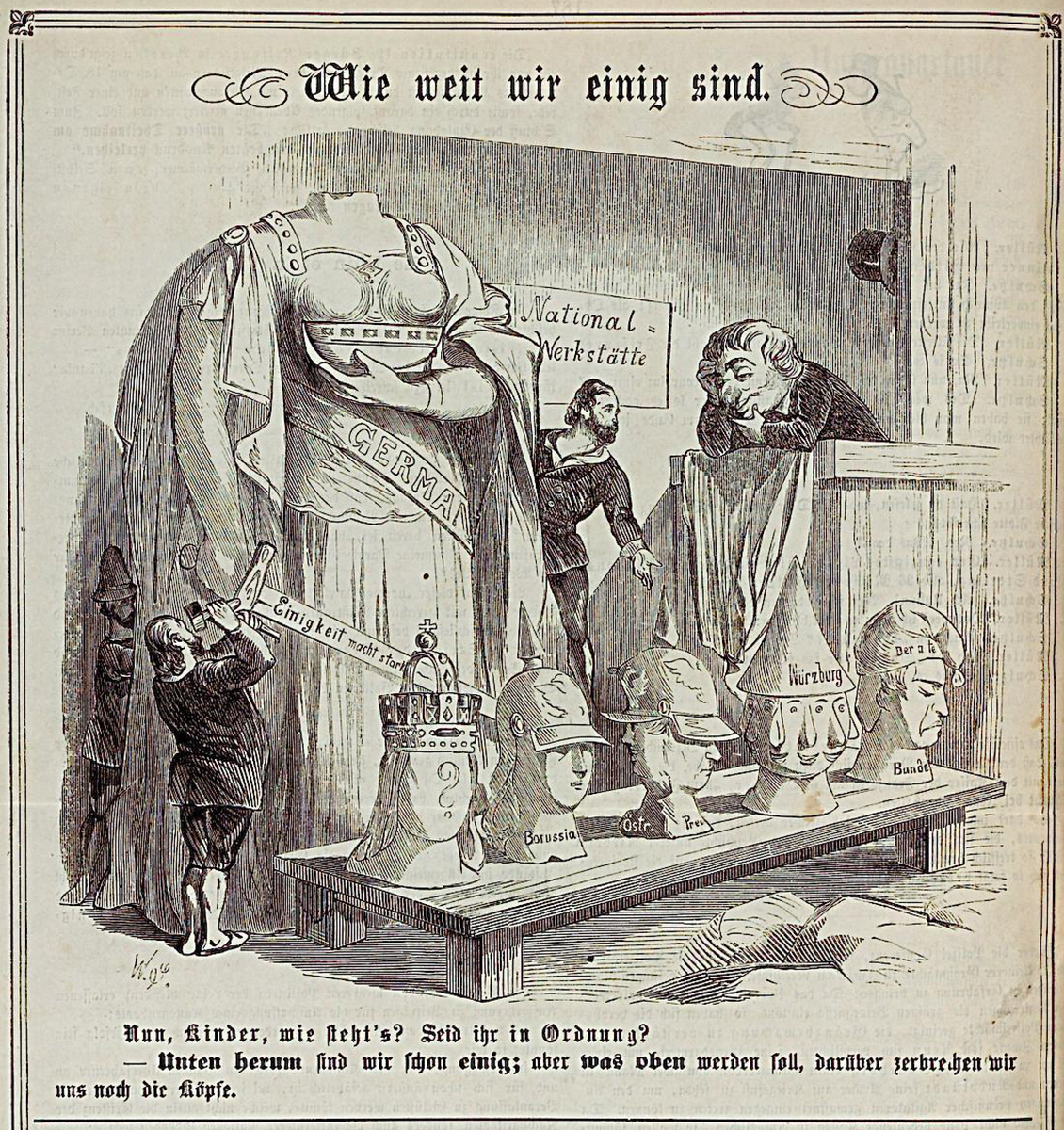

Political cartoons merged graphic art with social and political

commentary, seeking to amuse readers and sell copies of the journal in

which they appeared. Kladderadatsch,

founded in Berlin in the revolutionary days of 1848, was one the most

influential satirical journals of its time. This cartoon and the two

that follow show how image and text were combined to create memorable

impressions for the target audience. At the beginning of the decade, the

question of whether a “greater” or “small” Germany

[Großdeutschland or

Kleindeutschland] would emerge from

the struggle between Prussia, Austria, and the smaller federal states

was complicated by another question: what sort of political and

constitutional structure would the new state assume? The issue of

federal reform thus offered many possibilities—and little agreement—as

to which state, or group of states, would take the lead in proposing and

rallying consensus for a particular solution to the German question. In

this cartoon, the impish figure known as Kladderadatsch (top right)

visits the “National Workshop” ["National-Werkstätte"], where

German nationalists are busily sculpting the statue Germania. The legs,

arms, and torso are complete, and the figure already wields a sword

labeled “In Unity is Strength” [“Einigkeit macht stark”]. But the head

(of state) has yet to be chosen among various options. The first option

(from left to right) is a head whose only distinct feature is a question

mark where the face should be. The next head is adorned with a spiked

helmet and labeled “Borussia,” meaning Prussia. The third, a Janus face,

seems to offer the possibility of an ongoing Austro-Prussian dualism.

The fourth, labeled “Würzburg,” refers to an 1859 plan devised in that

city by Saxony, Bavaria, Württemberg, and various minor states to

prevent both Austria and Prussia from monopolizing power by creating a

“Third Germany.” But a clown’s hat and other indicators suggest that

this option has already been recognized as unworthy. The last head wears

an old-fashioned nightcap, suggesting that “the old Confederation” [“der

alte Bund”] was not likely to fire the imagination of German patriots in

the new decade. Kladderadatsch inquires, “Well, friends, how are things?

Have you sorted it out?” The reply: “We’re

agreed on the bottom part but still

racking our brains about the

top.”