Source

“Pre-Democratic Conditions in Brussels”

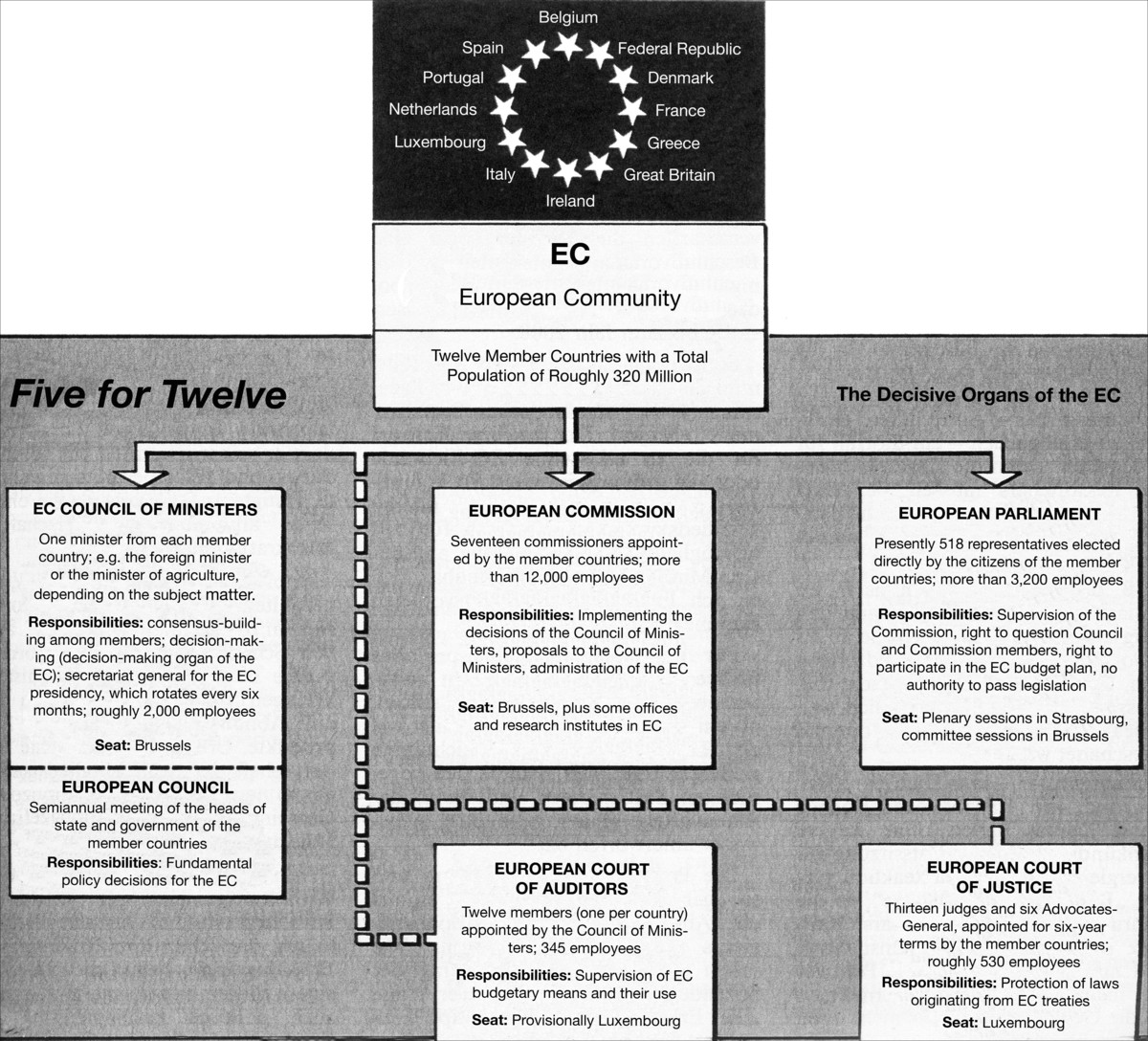

The European Community has become a mighty economic power, and with the Single Market in 1992, it will be even more imposing. Americans and Japanese fear “Fortress Europe.” It is not, however, the citizens or their elected politicians who have the say in Brussels but rather the legions of national and European civil servants. The European parliamentarians who will be elected on June 18 have little influence in the Community, the economic bosses all the more.

They were deluded and enmeshed in eternal enmity; they seemed condemned to absurd battles of faith and murderous wars of conquest—to a systematic self-destruction of their own making.

But now the Europeans are suddenly in top form. A Europe of superlatives is taking the stage and running for election: When 243.7 million citizens from Faro in southern Portugal to the Danish city of Skagen, from Galway in Ireland to Samos in Greece are called upon to vote for a common parliament in mid-June, the Community will project a more powerful profile than ever before in its 32-year history. Three hundred and twenty million consumers are able to spend a domestic product of eight trillion marks. World champions in importing, first-class in exporting. And everything is supposed to get even bigger, better, and more beautiful when the borders within the Single Market fall on December 31, 1992.

[…]

The fourth European election, the third direct one, the first in the expanded Community of Twelve, is at the same time the first to be held amidst high political tensions. How powerful will the new International of the European ultra-right be on June 19? How shriveled Bonn’s Helmut Kohl?

But who will determine this Europe, which according to the chancellor’s prognosis “will no longer be recognizable in ten years”? Who will decide on standards, regulations, and guidelines that will continue to profoundly change the everyday lives of EC citizens, [that will] intervene in the production of industrial corporations and mid-sized companies, channel trade, and coordinate currencies?

Not the representatives elected on June 18 from roughly 160 parties, not even the powerful heads of state and government who celebrate their all-too-frequent summit conferences. Rather, thousands of civil servants from the member states and the Euro-metropolis of Brussels will shape the future face of Europe and lay down European law. Guidelines and regulations will be proposed by public servants, negotiated by public servants, and resolved by public servants. The new Europe lies in the hands of one of the oldest powers on the old continent: the bureaucracy.

The EC Commission in Brussels, with its seventeen commissioners and twenty-two directors-general, is the only agency in the Western world that has the right to draft laws without having the democratic legitimacy to do so. The Council of Ministers, the highest decision-making body in the Community, only issues general guidelines or framework conditions. It’s the Eurocrats who are responsible for implementing them in detail.

When ministers from the twelve capitals vote on a new directive in the Charlemagne Building in Brussels, they usually feel the same way that former Bonn Minister of Health Rita Süssmuth did. In the EC capital, she felt that she had been degraded to a “mouthpiece for benevolent public servants.”

On her left, a deputy EC ambassador from Germany whispered in her ear; on her right, a high-ranking expert prompted her. And immediately behind her she knew of at least four ministry officials who were ready to jump at any moment to expound upon the complex issues at hand and provide her with tactical suggestions. On the table were the written stage-directions, her speech sheet, which not only dictated the course of the meeting, but also told her exactly what she was to say about certain agenda items.

Democratic control does not take place within this imposing alliance of Western European democracies. Although European parliamentarians are allowed to express their opinions on new guidelines, neither the Council nor the Commission is obliged to take the parliament’s majority vote into account.

Members of parliament have no access to the offices in which the Community decrees all its binding guidelines and regulations, such as those concerning environmental norms and security standards, the mutual recognition of university diplomas, or the harmonization of tax laws.

When Social Democratic environmental expert Beate Weber once dared to enter the special ministers’ council, she was politely but firmly ushered out.

The reason being: the Council’s executive branch is at the same time the legislature. The ministerial bureaucracy, with its ministers and undersecretaries at the top, passes the EC laws without any disruptive participation by the parliaments.

Only a fraction of the new regulations is even considered by the ministers in their council sessions. Eighty percent of the provisions are negotiated in the 150 working groups compromised by the Council’s public servants and then passed in the EC ambassadors’ committee, a body of top-level diplomats.

The Eurocrats—they are not just the Commission’s 12,000 public servants who administer the EC budget, monitor the implementation of norms that are passed, and draft new regulations and agreements.

The Eurocrats—they are also the roughly 2,000 employees of the Council secretariat who are responsible for the orchestration of dozens of conferences of the various ministerial councils and the supervision of the working groups, as well as the completion of the preliminary work for the Council presidency—currently held by the Spaniards—which rotates every six months.

The Eurocrats—they are, finally, the divisions of Brussels-bound national civil servants who haggle with their Brussels colleagues behind the closed doors of the Charlemagne Building over the form of the Single European Market.

The minutes of the Council sessions are so “secret” that not even the members of the European parliament get to read them. “How can decisions be monitored at all with this way of doing things?” asks Social Democrat Thomas von der Vring. Bonn’s opposition leader Hans-Jochen Vogel also carps that “pre-democratic conditions” prevail in Brussels. When Europe’s citizens vote in June, they will only be deciding on the composition of the relatively powerless parliament in Strasbourg, not on the politics of the Community. Political policy is developed in the Commission, the (premier) EC administrative body, which has long been seen by both Bonn and Paris as a bastion of extraordinary inefficiency.

It was Jacques Delors of France—whom Chancellor Helmut Kohl referred to as “a European with an incredible background, a man of vision and engagement”—who finally ended the paralyzing Euro-sclerosis. By giving his public servants a new sense of mission and self-confidence, he of course also reinforced the already all-encompassing power of the bureaucracy.

He got the highly frustrated, highly paid bureaucrats in the Commission moving and brought the inefficiency of the EC authority to an abrupt halt. He pressured the agriculture minister to make serious cuts in price and purchase guarantees for agricultural products. And he convinced the heads of government of the twelve member countries to approve a new financing concept for the Community, so as to put the budget, which was in perpetual deficit, back on its feet.

But his greatest merit was to revive the economic community’s sense of political business, which its founding fathers inspired back in 1955: the vision of a Europe united not only economically but also politically, with no internal borders.

[…]

In contrast to the [West] German federal government, which has long used the Commission in Brussels as the final repository for flagging politicians and dubious bureaucrats, the French government has always placed great value on sending the most qualified personnel possible to the EC headquarters. After all, there are national interests to be defended in the European headquarters.

The British are also practicing calculated personnel politics, preferring to fill influential positions in the research departments, where English has asserted itself as the official language.

Greece and Luxembourg also replaced their weak commissioners with the career diplomat Jean Dondelinger and industry minister Vasso Papandreou—“first-class professionals” according to the Commission’s estimation.

[…]

Source: “In Brüssel vordemokratische Zustände,” Der Spiegel 23/1989, June 5, 1989, pp. 136–41. Republished with permission. Available online at: https://www.spiegel.de/politik/in-bruessel-vordemokratische-zustaende-a-03d36731-0002-0001-0000-000013493198