Abstract

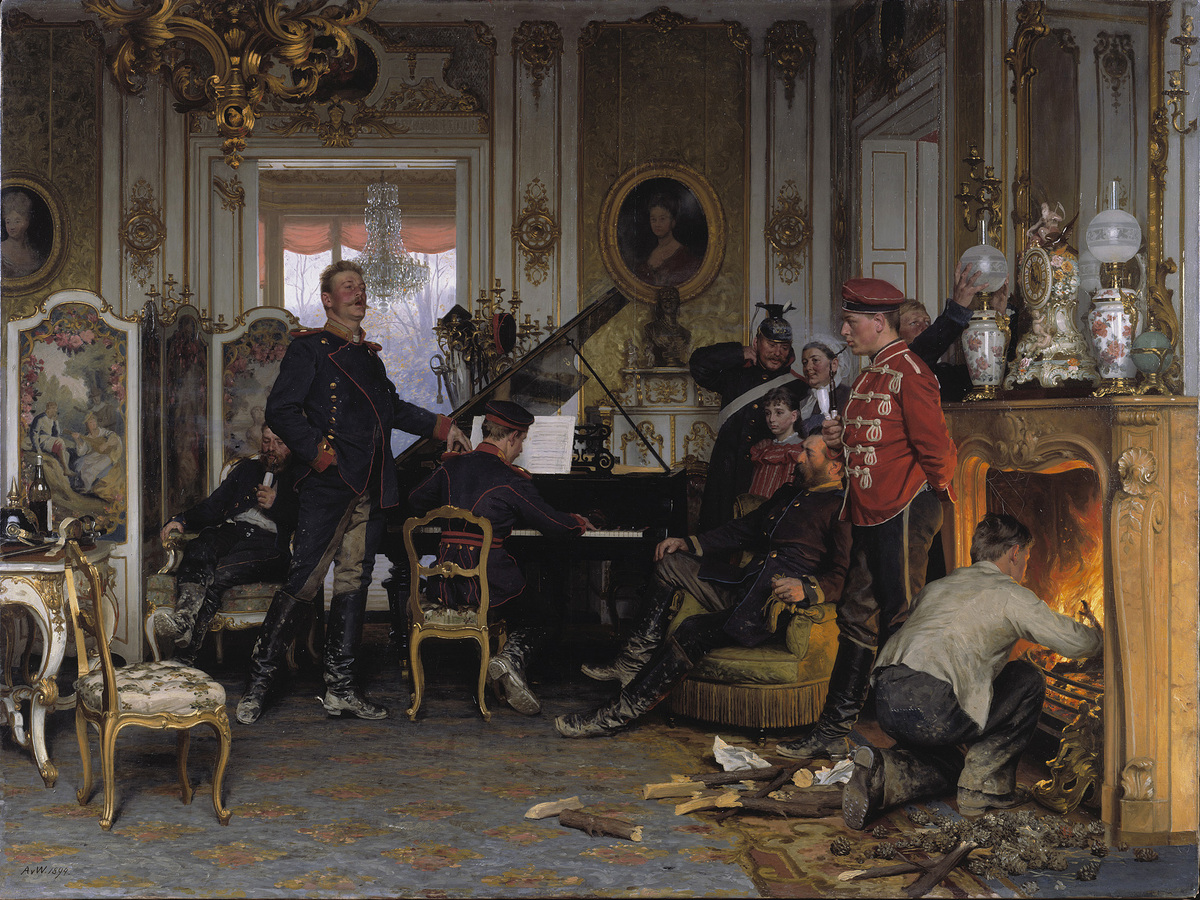

This painting by Anton von Werner (1843–1915) was completed in 1894

and purchased the same year by the National Gallery in Berlin (making it

the first Werner acquired by the gallery). The sketch upon which the

painting was based, however, had been executed twenty-four years

earlier: on October 24, 1870, when the artist accompanied Chief of the

Prussian General Staff Helmuth von Moltke (1800–1891) and his entourage

in occupied France. The final work shows German troops occupying the

Château de Brunoy outside Paris during the Franco-Prussian War. To be

sure, Werner documents every detail of the scene and the setting—right

down to the inexpertly repaired boot sole at the right. But his

principal aim is to emphasize the contrast between the vigorous,

ruddy-cheeked troops, with their practical mud-covered footwear, and the

sumptuous, effeminate interior they have requisitioned for temporary

lodgings. This contrast is conveyed not least by Werner’s palette—the

soldiers, dressed in blue uniforms with red piping, are rendered in dark

primary colors, thereby standing out against an interior awash in

pastels and dominated by the warm yellow of gilded surfaces. In this and

other pictorial choices, Werner seems to suggest German cultural

superiority over the French. For example, the soldiers have not, as in

the age-old manner, destroyed the furniture at hand to light a fire and

revenge themselves on the enemy; instead, they have taken the time to

gather wood on the villa’s grounds, seen just outside the window at

rear. And while the soldiers look dirty and rumpled, they are not

necessarily rough-hewn. In fact, they have enough good German

Bildung—education and

“cultivation”—to play the piano and give voice to song in an impromptu

concert. (According to Werner’s notes, they were singing Franz

Schubert's setting of Heine's poem “Das Meer erglänzte weit hinaus”

[“The Sea Shone Resplendent far into the Distance”], which, as he added,

was very popular with all the military bands at that time). This history

lesson would not have been lost on German viewers of the painting in

1894. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to portray Werner’s politics as

illiberal or chauvinist. He had no need to make the enemy appear

despicable: except for the villa’s female concierge and her daughter,

who appear to be suffering none of the hardships inflicted upon the

Parisian population at the time, the French have simply disappeared from

the scene. The mood of good humor is further reinforced by the elaborate

clock and vases on the mantle—their very presence suggesting that no

looting has been committed by the occupying troops. These choices make

the painting even more melodramatic and contrived, undercutting its

apparently disinterested virtuosity. What conclusions do we draw from

this? On the one hand, the very fact that patriotic painting of this

sort had achieved such popularity by the 1890s may indicate that, by the

turn-of-the-century, the chauvinism so vehemently criticized by

Friedrich Nietzsche after 1871 had evolved into something that was, if

not more generous to French victimhood or forgiving of German brutality,

then at least more innocuous. Tellingly, when contemporary viewers

commented upon Werner’s portrayal of soldiers lounging disrespectfully

on the furniture of a beautiful French château, they found this aspect

amusing, not offensive. On the other hand, such public reaction may

reflect the philistine complacency that Nietzsche also identified as

characteristic of post-unification German society.