Abstract

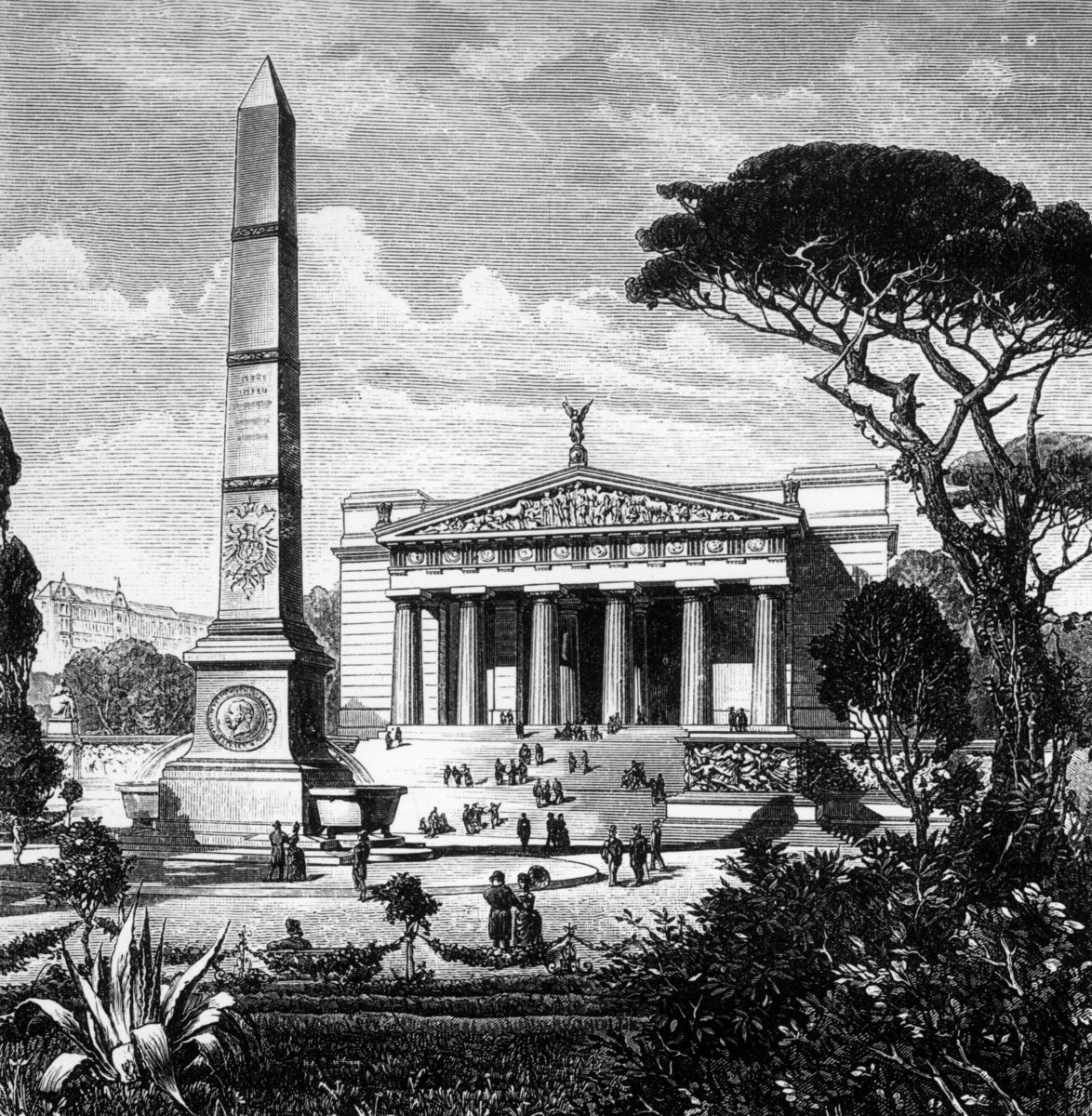

This woodcut shows the central exhibition grounds for the Jubilee

Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts in Berlin, which was held from

May to October 1886. In the background, we see the Temple of Zeus, which

contained the Pergamon Panorama. Halfway up its staircase is a replica

of the massive Pergamon altar. Not shown is the immense Egyptian temple

(40 meters long and 20 meters deep), whose five dioramas celebrated the

role of Germany and other nations in African colonization. Also omitted

is the great iron and glass exhibition hall, which featured giant

canvasses by Anton von Werner (Congress of

Berlin, 1881), Adolph Menzel

(Coronation of King Wilhelm I in

Königsberg, 1865), and other artists, German and non-German alike.

(No French paintings were included in the exhibition, because the

French, citing the Germans’ non-participation in the Paris Universal

Exposition of 1878, refused to send any works.)

As many as 20,000 people are said to have visited the Jubilee

Exhibition on a single evening, June 6, 1886, and according to reports

it attracted more than 1.2 million visitors before closing on October

31, 1886. An uncontested box-office success, the exhibition generated a

profit of more than 15,000 marks from total revenues of 70,000 marks. In

the eyes of Prussian Minister of Culture Gustav von Gossler, the

exhibition had also shown the rest of Europe that “art had gradually

taken up its dwelling among us, had found in the north a firm home.”

(Beth Irwin Lewis, Art for All? The

Collision of Modern Art and the Public in Late-Nineteenth-Century

Germany. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003, p. 97). Hopes

that the exhibition had finally displayed a “unified” German art,

however, went unrealized. In fact, throughout the 1880s, Berlin figured

only marginally in a German art scene characterized by regional

distinctiveness and competition—as Munich’s Third International Art

Exhibition in 1888 made abundantly clear.