Abstract

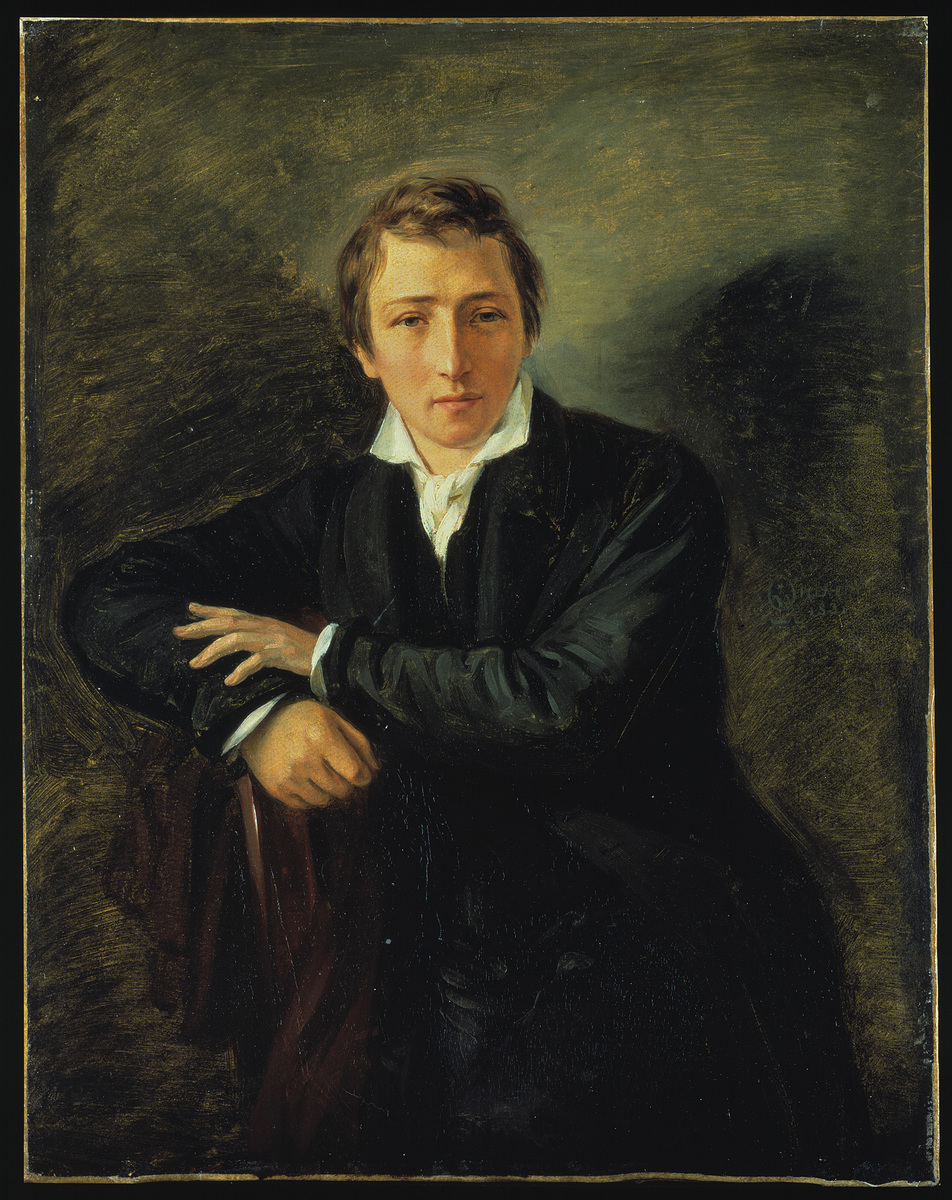

Heinrich Heine (1797–1856) was one of the most important German poets and journalists of the 19th century. The roots of his style can be found in Romanticism, a movement that he eventually progressed beyond, however. By the beginning of the 1830s, Heine had established a reputation as a successful poet both within the German states and throughout the rest of Europe. Nonetheless, he was also regarded as an outsider on account of his Jewish heritage and his criticism of the policies of the German Confederation, and many viewed him with hostility. His political views, and above all the strict censorship of his works, prompted him to leave Germany in 1831 and settle in Paris, where he turned increasingly to journalistic writing. In 1835, what began as emigration ended as exile, when his works were banned in the German Confederation. Heine shared this fate with the writers of “Young Germany,” a group of young authors who espoused similarly liberal views. (Although Heine did not consider himself a member of this group, the authorities did.) Despite Heine’s friendship with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, he never regarded himself as an adherent of a particular party or movement; for him, the independence of the critical intellect always stood at the forefront. Although Heine was among the sharpest and most vocal critics of the German Confederation, he was also skeptical of the forces of the revolutionary movement. In his own time, the potential dangers of a seething German nationalism were already more than apparent to this prescient author, whose own works would be banned and burned by the Nazis a century later. Painting by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800–1882), 1831.