Abstract

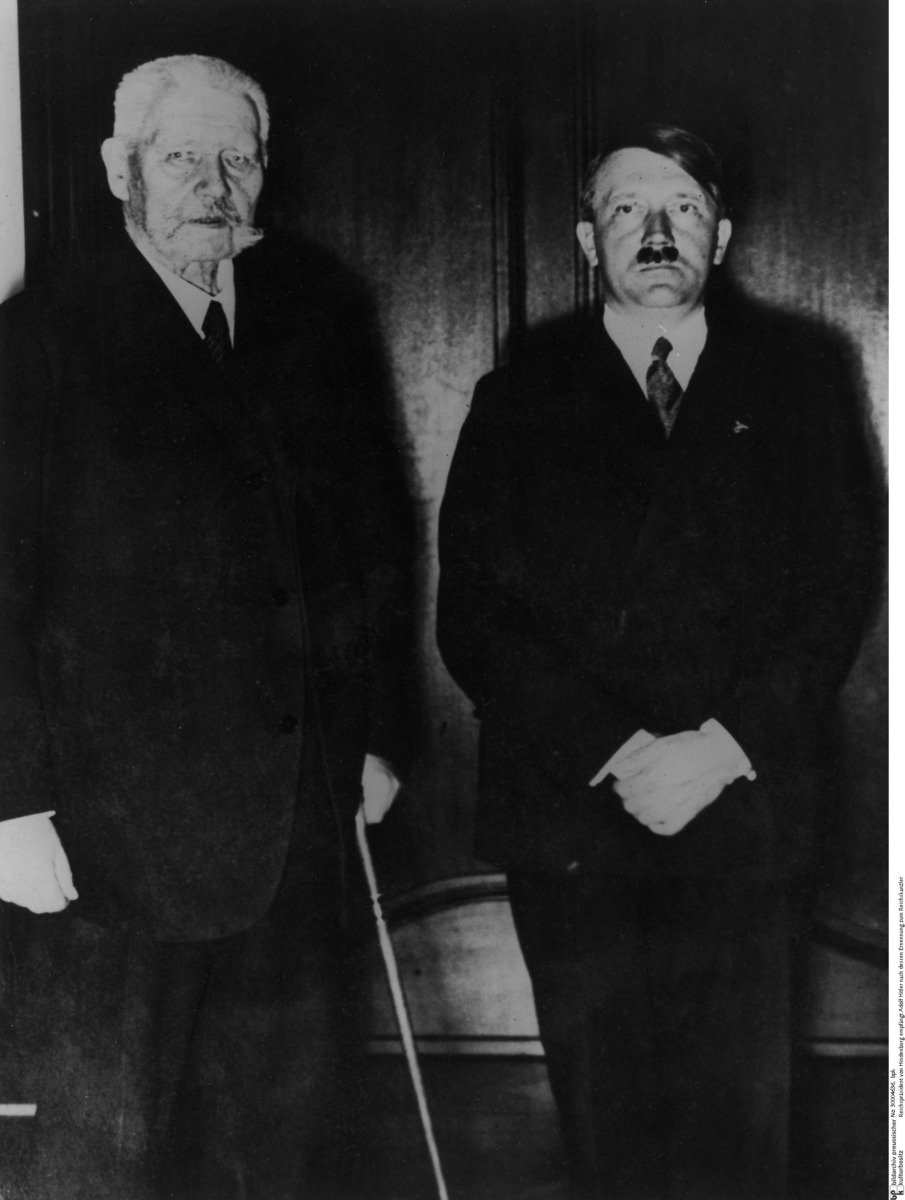

In 1925, the revered war hero General Field Marshal Paul von

Hindenburg (1847–1934) was elected Reich President at age 77. (In 1932,

he was re-elected to the same office for a second seven-year term.)

Hindenburg’s election meant that a convinced monarchist became head of

state in the Weimar Republic. Accordingly, the political center of

gravity shifted increasingly to the right. Nonetheless, the years

1924–1928 were still marked by relative stability in political,

economic, and social affairs. It was only in 1929 that the incipient

worldwide economic depression upset the fragile balance of Germany’s

first democracy. The breakdown of the “Grand Coalition” in March 1930

was followed by an ongoing governmental crisis, during whose course

Hindenburg made ever greater use of the emergency powers granted to the

president by the Weimar Constitution, essentially replacing

parliamentary government with a de

facto presidential dictatorship. The conservative, elitist

Hindenburg had little sympathy for the Nazi party’s vulgar brand of mass

politics. He felt a strong personal and political dislike for Adolf

Hitler, whom he disparaged as the “Bohemian private.” But Hindenburg’s

aversion to Social Democrats and Communists was even stronger. Moreover,

the NSDAP had emerged as the strongest party in the last free Reichstag

election on November 6, 1932, securing 33.1 percent of the vote. In

January 1933, after the failure of the fourth presidential cabinet in

two years, former chancellor Franz von Papen resumed negotiations with

Hitler and persuaded President Hindenburg to agree to a new coalition

government under Hitler.