Abstract

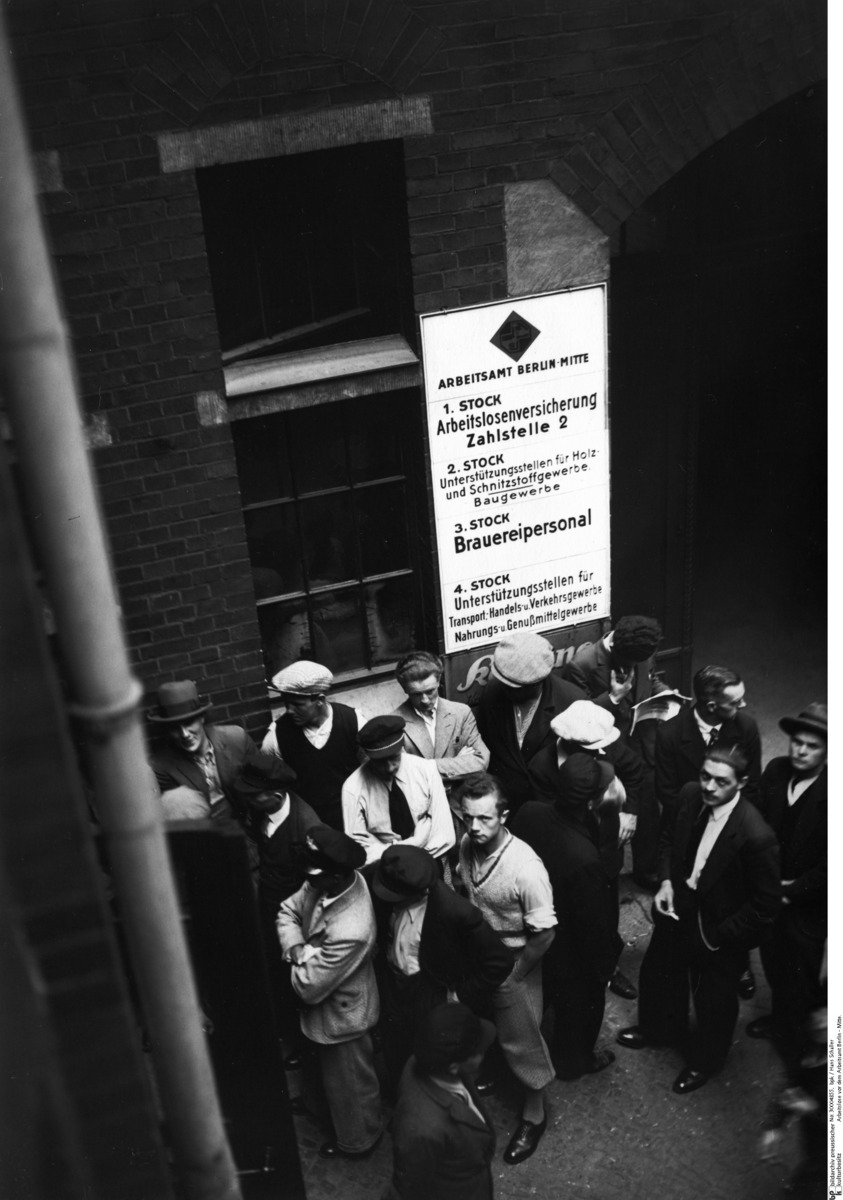

The persistent worldwide depression and the mass unemployment

associated with it were among the main catalysts for the general

radicalization of the political climate in Germany—a process from which

the NSDAP benefited more than any other party. In 1932, when the crisis

reached its peak, about 6 million people were registered as unemployed

in Germany. Together with their families, they constituted at least

one-fifth of the population, and the true number of those affected was

probably higher. Women, for instance, often failed to register with the

authorities when they were dismissed from positions. Furthermore,

millions of workers who kept their jobs often had to accept drastic

decreases in their salaries and hours. No sector of the economy and no

stratum of the population was spared, but industry was hit particularly

hard. Between 1928 and 1932, the number of unemployed in Berlin (then

Germany’s largest industrial center) rose from 133,000 to 600,000; in

Hamburg, from 32,000 to 135,000; and in Dortmund from 12,000 to

65,000.