Source

The Hesse Coalition: “Just What Willy Wanted”

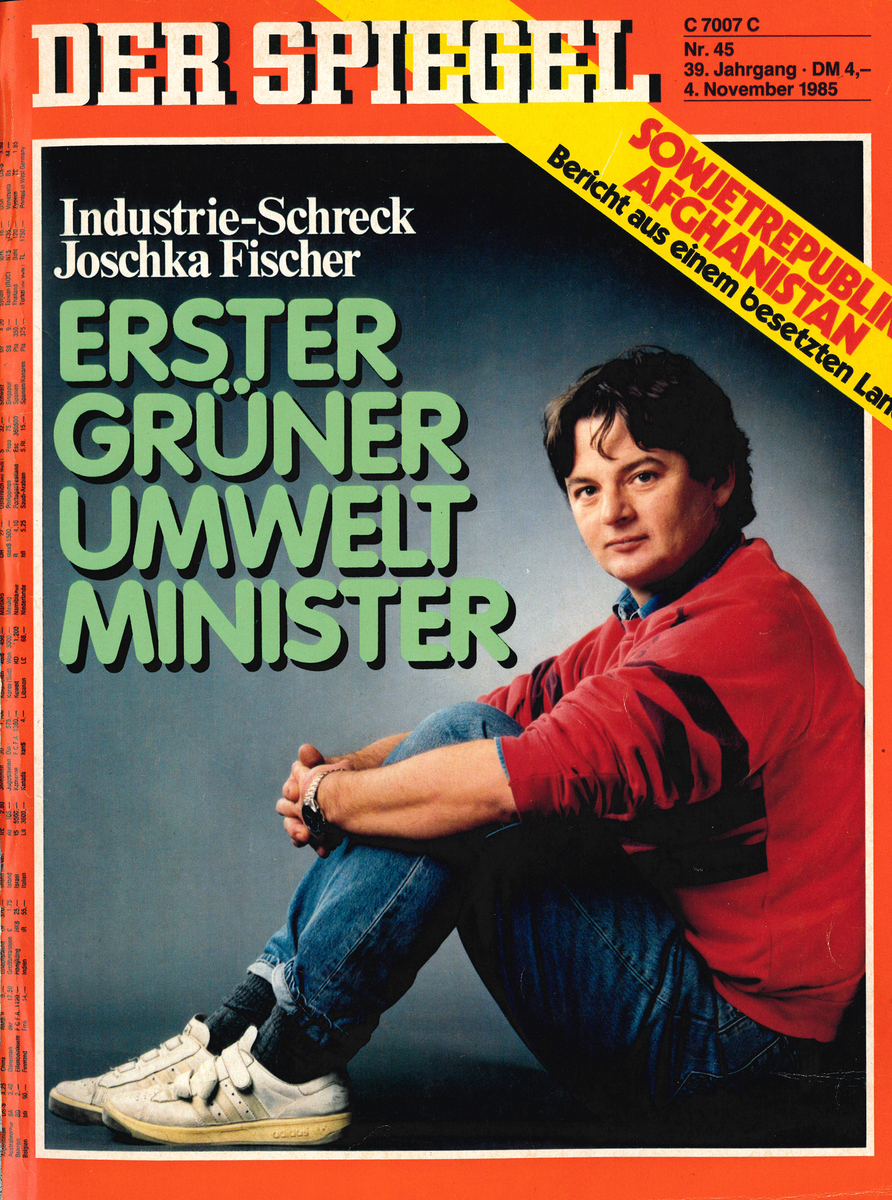

He walks out of the supermarket quietly, in sneakers.[1] The blue jeans are worn; the sweatshirt, red, is faded; the leather jacket, scruffy. The man looks like a cross between a roadie and rowdy. His dog Dagobert prances around him.

There are gray shadows under the alert eyes (red veins and all) of his pale, somewhat bloated face. His dark, tousled hair is unkempt; he shaves only once a week, on Mondays.[2]

He is a fanatic marathon-debater, an agitator; he speaks with a bright, penetrating voice and a slight Frankfurt accent. His speeches are often peppered with mostly challenging thoughts. When he reviles and insults adversaries, he does so with great relish.

Everything about Joseph (“Joschka”) Fischer, 37, fits the typical, upstanding citizen’s image of a flipped-out revolutionary. And when, in the near future, the official car of the Minister of the Environment pulls up to the Hessian state chancellery, there could be some confusion: the distinguished gentleman in the gray suit and tie—that’s the chauffeur. The fellow in the back seat who looks like an informant for the Ruhr valley bully Schimanski[3]—that’s the minister.

Some people can hardly believe it. A New Left activist—a Sponti[4]—from the Frankfurt squatters’ movement, a Realo-Green[5] with a coarse proletarian attitude, a former drug user with a record, a man dressed in the baggy-look takes a seat at the cabinet table—as Minister for the Environment and Energy.

Since the Hessian Green Party agreed to form a government coalition with Holger Börner (SPD), thus sealing the first eco-social coalition in a federal state, the political climate in Germany has changed. Businessmen, conservative politicians, and editorial writers are falling into line, as if there were some sort of coup to defend against.

Managers dismiss the minister-to-be as a nightmare for industry. They threaten to stop investments in Hesse and announced that businesses would flee to neighboring states. Hans Joachim Langmann, president of the Federal Association of German Industries and head of Merck Pharmaceuticals in Darmstadt, explains big business’s fear of the Greens: With Joschka Fischer, “someone who, up to now, has proven himself as hostile to business and industry in all of his statements, holds the lever of political power.”

Federal Chancellor Helmut Kohl did not even care to utter the name of the ministerial candidate. He was “anxious to see,” scoffed the government chief, “how this Bundestag genius, what’s his name again,” will turn out as a minister. If the Hessian model were applied to Bonn, prophesied CDU general secretary Heiner Geißler, it would lead to the “collapse of the German economy.”

“Hesse,” wrote the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, is “not only in danger of gambling away the present, but even more so the future.” Bild Zeitung lamented: “We’re afraid for Hesse.”

Even the Reds[6] and the Greens themselves showed skepticism. Minister President of North Rhine-Westphalia Johannes Rau, a declared adversary of the Alternatives[7], complained that Börner ruined his campaign strategy. SPD trade union man Hermann Rappe warned that the new coalition partners are “harmful for employees in the long run.”

Green Party chair Rainer Trampert, a “fundamentalist” Green, predicted a “schism” in his party “along with parts of the social movement.” At the university in Frankfurt, leftist radicals threw eggs at old-leftists Daniel Cohn-Bendit and Joschka Fischer for being willing to form a coalition, and they put them in the same boat with Hessian interior minister Horst Winterstein, whom they blame for the death of demonstrator Günter Sare: “Fischer, Bendit, Winterstein—one swine is just like another.”

From now on, Fischer’s political fortunes will also direct the path of the Greens. If the first alternative minister can show the republic that Green environmental policies can be implemented in everyday government, then his party can count on new supporters. If Fischer fails, it could speed the decline of the Alternatives, who recently failed to clear the five percent hurdle in Saarland (2.5 percent) and North Rhine-Westphalia (4.6 percent).

A street fighter who turned himself into a real politician, who first became a Bundestag representative and then a minister, after years of refusing to hold office—this is an indication of the maturation process of the youngest West German party. Six years after its founding, the “anti-party party” (Petra Kelly) has made its way from a statistical “majority this side of the CDU” (Willy Brandt) to a political one.

The beneficiary is Holger Börner (“This story will get me 50,000 young voters”), who was warmly welcomed in the party’s presidium last Monday by the SPD party chairman. “I am the only one,” the Hessian said interpreting the friendly reception, “who did just what Willy wanted.” Like Brandt, Börner also set his sights on the immediate goal—along with an SPD minister president in Lower Saxony—of breaking the CDU majority in the Bundesrat in the spring, in order to make it more difficult for Kohl to govern.

To be sure, Lower Saxony’s leading candidate, Gerhard Schröder, does not want to adopt the Hessian model, but other leading Social Democrats support Börner’s course. SPD presidium member Erhard Eppler defends the Red-Green coalition, pointing to Saarland’s SPD Environment Minister Josef Leinen, who, like Fischer, aims to bring economy and ecology together under one roof. “Why is a Joschka Fischer in Hesse any different from a Jo Leinen in Saarland?”

The difference lies in their personal histories. In the Bundestag handbook, where representatives like to elaborate on the number of offices they hold and all they can do, Fischer—a Bundestag representative for the Greens until March 1985—needed no more than two lines: “Born on April 12, 1948. Member of the Bundestag since 1983.”

That reads as though nothing much happened during the years in between—and as though he wanted to distance himself from his life. But Fischer does not reject his own history: “Except for what is in my file at the Office for the Protection of the Constitution, I have nothing to hide. I stand by my history.” Joschka, raised in the strictly Catholic town of Fellbach on the outskirts of Stuttgart, stems from “a family of butchers.” Father and grandfather were meat dealers, “full time,” and of course “Catholics.” Joschka, however, was not altar boy material, well-behaved in a red and white robe, so he became a bicycle racer.

In the tenth grade, he had had enough of Gymnasium and began to have “a lot of fun” with a photography apprenticeship. The fun lasted a year. Turned on by Bob Dylan and the Beatles, he indulged in the 1960s “new attitude toward life,” and at sixteen he fled “the narrowness of home, village, and apprenticeship.”

The police picked him up in Hamburg and carted him back to Swabia. On his second attempt at a “European tour” he got as far a Kuwait—a non-conformist from an early age.

Back at home, runaway Joschka had a job for a short time as an assistant clerk at the employment office, in the child benefits department. A second attempt at a photography apprenticeship also failed.

That was the time when Ludwig Erhard was still chancellor, who insulted intellectuals who mocked him as “pinschers.” Joschka read Jack Kerouac, the Beat Generation’s man of letters, and fell “madly” in love with Edeltraud, a seventeen-year-old Swabian. Still minors, the two married in 1967 in Scotland’s Gretna Green.

Fascinated by the student protests against the Vietnam War and full of rage over the death of demonstrator Benno Ohnesorg and the assassination attempt on Rudi Dutschke (Fischer: “the shots in Berlin awakened me”), the young newlyweds moved to Frankfurt. There, in one of the metropolises of student revolt, the young Gymnasium student with no degree and no training wanted to go back and get his diploma in order to study Kant, Marx, and Hegel at Johann Wolfgang Goethe University.

[…]

The Swabian outsider quickly fell into the center of the left-liberal scene on the river Main. SDS leader Hans-Jürgen Krahl was mentor to the butcher’s son; the revolutionary perspective he learned from comrades like De Gaulle challenger Daniel Cohn-Bendit, sex researcher Reimut Reiche, SDS ringleaders Frank and K.D. Wolff, Matthias Beltz (today “Vorläufiges Frankfurter Fronttheater”), and the banker’s son Tom Koenigs, a Frankfurt city councilor and Fischer’s soon-to-be budget expert in the Ministry of the Environment.

Together with other activists, the Spontis founded a militant group, the “Revolutionäre Kampf” (Revolutionary Struggle or RK). Fischer, whose rhetorical talent had impressed the university-educated group members, was asked to become one of their spokesmen. “Joschka,” as the former SDS leader and RK-fighter Frank Wolff recalls, “was best at striking the right tone,” plus he “had a certain proletarian aura.”

The Swabian rebel was always in the forefront during the “terrible time of open revolts,” from 1968 to 1975. “It went through all the different stages right up to heavy rioting,” and Joschka was “the warrior chief” of the Frankfurt street battles, quick with his tongue and fast on his feet.

[…]

Very early on, Fischer identified the murderous terror of the Baader-Meinhof Group as the “wrong track” (Koenigs). Achieving social change through bombing was not his thing. The street fighter’s opinion of Red Army Faction (RAF) leader Andreas Baader: “He made me want to puke.”

In the Frankfurt Römerberg[8] in June 1976, Fisher made his first major speech after the death of Ulrike Meinhof. He called for a “break with the armed struggle”—shortly afterwards two RAF bombs went off in Frankfurt’s U.S. [military] headquarters. Fischer at that time: “We cannot follow the urban guerillas. RAF actions mean renouncing life, fighting to the death, and therefore self-destruction.”

The call by the head Sponti (“Comrades, throw away the bombs and take up stones again”) marked roughly the beginning of the end of the RAF terror. Koenigs said that “Joschka separated the alternative political scene from the RAF.”

[…]

One of the toughest street fighters, of all people, was also one of the first to join the newly forming, gentle Green movement. It was “a shock for many.” Fischer suddenly saw “options in real politics,” and the “Sponti and Marxist who believed in progress” became a Green.

Fischer broke with the Spontis (“they were finished”). After the Greens’ success in the 1981 local elections in Hesse, when fundamentalist [Fundi], oppositional Greens held sway in the Römer[9], Fischer started directing the group of realist [Realo] politicians in the Green district chapter. “We can’t just go on preaching in the parliament that time is running out and refuse to take on responsibility.”

The Fundis, who reviled him as the “top macho,” goaded his sense of ambition. Joschka fought his way to third place on the state list of candidates before the 1983 Bundestag election and on the morning after the election, he said, “I woke up as a member of the Bundestag.” Fischer: “My new foray into reality.”

[…]

As a speaker, Fischer had dazzling moments in the Bundestag. He still considers his debate contribution to Wörner’s Kießling scandal,[10] in which he mocked Kohl’s spiritual, moral renewal as “a Palatinate work of art, sinking slowly into baroque opulence,” as one of his historic moments in parliament: “Politics as real-life comedy.”

When Heiner Geißler denounced the pacifism of the 1930s as a cause for the Nazi horrors at Auschwitz, Fischer struck back with polished rhetoric. After the death of the Turk [Cemal] Altun, who jumped to his death to avoid custody pending deportation, Fischer transformed himself into the defender of asylum rights. Heinrich Böll referred to the two debate contributions as “the best speeches given in the Bundestag in years.”

“As a symbol,” said Hubert Kleinert, Fischer’s Realo companion from Marburg, “he was incredibly important for us in Bonn: unshaven and in jeans, he represented, on the one hand, the lifestyle of a large group that had never before been represented politically in Bonn. And on the other hand, he brought life to the Bundestag and became a symbol for left-liberal intellectuals.”

Faster than other Greens, Fischer adapted to the habits of the politicians in Bonn and transformed himself into a media favorite. But he worked just as hard on the image of the non-conformist. The CDU/CSU representatives confirmed that for him by shouting “pinstripe punk,” “rogue,” and “despicable loudmouth” during his speeches.

[…]

As the “defender of the environment,” Fischer says statesmanlike, he “will not assert himself through ordinances or directives, but through persuasion,” in order “to achieve as much consensus as possible, even with big business.”

Fischer and his comrades-in-arms have long since agreed on a moderate pace in their new office. “We won’t make a fuss,” appeases Green speaker Georg Dick. “Everything,” says Fischer, “is done according to law and statute”—which spurred SPD economics minister Ulrich Steger to the assessment that, in comparison with Fischer, “even Young Socialists seem revolutionary.”

But a minister who strictly abides by the environmental laws—that is exactly what Hessian industrial managers seem to be afraid of.

Friedrich Karl Janert, CEO of the Hessian Chemical Employers Association: “If Fischer follows the environmental protection laws to the letter, it will be torture.”

Notes

Source: “Hessen-Koalition: ‘Wie Willy wollte,’” Der Spiegel, November 4, 1985, pp. 24–31. Republished with permission.