Source

Source: "Reichstag," Meyers

Konversations-Lexikon, 5th ed., Leipzig,

1899.

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_NrUfAQAAIAAJ/page/n877/mode/2up

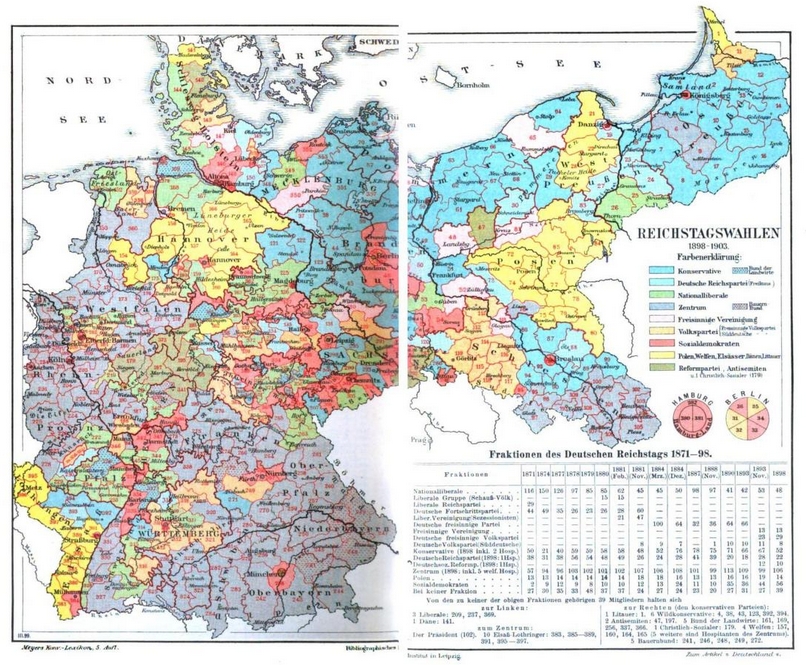

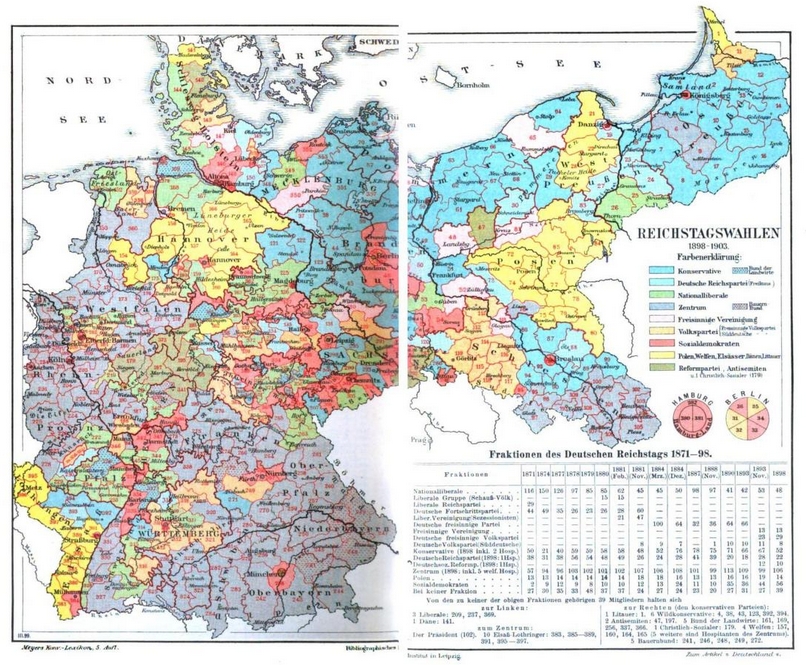

This colorful electoral map from the popular 17-volume German encyclopedia Meyers Konversations-Lexikon lays out the complicated election results from the German Federal Elections of June 1898. The colors show the dominant political party for every electoral district of Germany.

The party names translate as:

Conservative Party [a right-wing

party, representing the interests of the nobility/Junker

elites]

German Reich Party (Free

Conservatives) [a right-wing party, politically situated between the

Conservatives and the National

Liberals]

National Liberals [a

right-wing liberal party]

Center

Party [party for Catholic interests, generally

center-right]

Liberal People’s

Party (Freisinnige

Vereinigung) [moderate liberal

party]

People's Party

(Volkspartei) [moderate liberal

party]

Social Democrats [left wing

party of the working class]

Polish,

Welfs, Alsatians, Danes, Lithuanians [special-interest regional

and/or ethnic parties]

Reform Party

& Anti-Semite Party [single-issue antisemitic parties on the

far right]

This map illustrates a number of political complexities.

First, most of the major parties drew upon regional strengths. The (Catholic) Center Party, for instance, was preeminent in the Bavarian countryside of south-west Germany, while the Conservatives dominated in rural East Prussia. Central Germany and the Rhineland were more liberal. The Social Democrats, meanwhile, won in cities like Hamburg and Berlin, and other industrial towns like Mannheim or Elberfeld-Barmen (which later became Wuppertal).

Secondly, although there were 5 main political parties (Conservative, National Liberal, Catholic Center, Liberal, Social Democrats) there were a plethora of splinter parties, including special-interests parties for Polish-speakers, for Alsatians, for Danes, for Hannoverian separatists (Guelph/Welfen), for rural farmers, and so forth. These splinter parties in the Kaiserreich presaged those splinter parties that would plague German electoral politics in the Weimar Republic of the 1920s.

Thirdly, the inset chart “Factions of the German Reichstag, 1871-1898” shows the fortunes of the various parties over time. We can see the steady decline of the National Liberals, who had been the dominant party in the 1870s (supporting Bismarck's Kulturkampf against the Catholics as well as his Anti-Socialist Laws), but lost that position in 1880 when their left wing split off; by the 1898 elections, the National Liberals were now largely the ally of big business interests. Likewise, we see the decline of the Conservatives as well, after their heyday in the mid-1880s. And we see the gradual but steady rise of the Social Democrats, which, after the 1898 elections, became the second largest party in the Reichstag.

Equally important, however, is what the map does not depict: the strength of the Social Democrats in the popular vote. In 1898, the Social Democratic Party received the most votes in Germany—over 2,107,100, or 27% of the total. Because of the vagaries of the electoral districting system (with first-past-the-post rules for each district) the Social Democrats received only 56 seats (of 397). Meanwhile, the largest party in the Reichstag, the Catholic Center Party with 106 seats, had only 18.8 % (1,455,100) of the popular vote – half a million fewer votes than the Social Democrats, but almost double the seats, because of favorable districting.

Source: "Reichstag," Meyers

Konversations-Lexikon, 5th ed., Leipzig,

1899.

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_NrUfAQAAIAAJ/page/n877/mode/2up

Internet Archive