Abstract

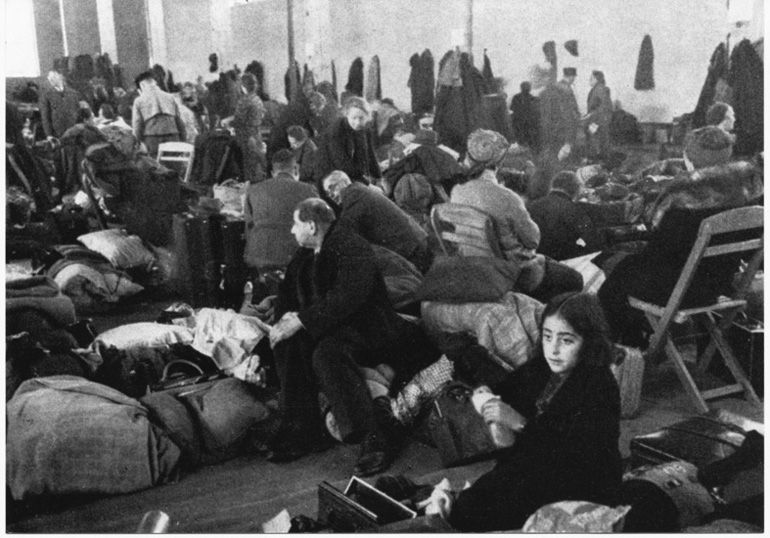

Until 1941, the Nazi regime pursued the goal of a “Jew-free German

Reich” through mass deportations and expulsions. Between October 1939

and January 1940 alone, 78,000 Austrian and Czech Jews were forcibly

resettled in the Polish district of Lublin. In certain cases, German

Jews were also deported to Western Europe. For example, in October 1940,

the Gauleiters of Baden and Saarland-Pfalz organized the deportation of

6,500 Jews to occupied France. At the same time, the “Reich Center for

Jewish Emigration” (which was set up in the interior ministry after

Kristallnacht) worked to promote

Jewish emigration out of the Reich. But with the German invasion of the

Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, Nazi Jewish policy in the German

Reich took a dramatic turn. As of October 23, 1941, Jews living in the

German Reich or in occupied areas were prohibited from emigrating. They

were no longer to be driven out of the German sphere of power; rather,

they were to be transported en masse

to the occupied areas of Eastern Europe for the “final solution of the

Jewish question.” The systematic “resettlement” of Jews from the German

Reich began on October 16, 1941. Only a few weeks later, the first of

these Jews were killed in mass shootings near Kaunas (Lithuania) and

Riga (Latvia). Other German Jews, together with Jews from all over

Europe, were either deported to ghettos in the east or sent directly to

concentration and extermination camps. According to data assembled by

the “Reich Union of Jews,” 164,000 Jews were living in the old German

Reich in October 1941. By July 1944, only an estimated 14,500

remained.