Abstract

As the regime’s public persecution of Jews and other so-called

undesirables increased in intensity and brazenness in the late 1930s,

its economic persecution of these groups progressed as well, albeit

through subtler means. As historians have noted, Jews suffered “social

death” long before they faced physical deportation and murder.

Understanding this social death means examining the ways in which

Germans encountered—and adopted—less overt forms of antisemitism in

their everyday lives. This culture of antisemitism led to many small

changes that, by themselves, would hardly have seemed surprising within

the greater context of National Socialist Germany. Nonetheless, these

small changes show how Jews were increasingly isolated from the rest of

German society.

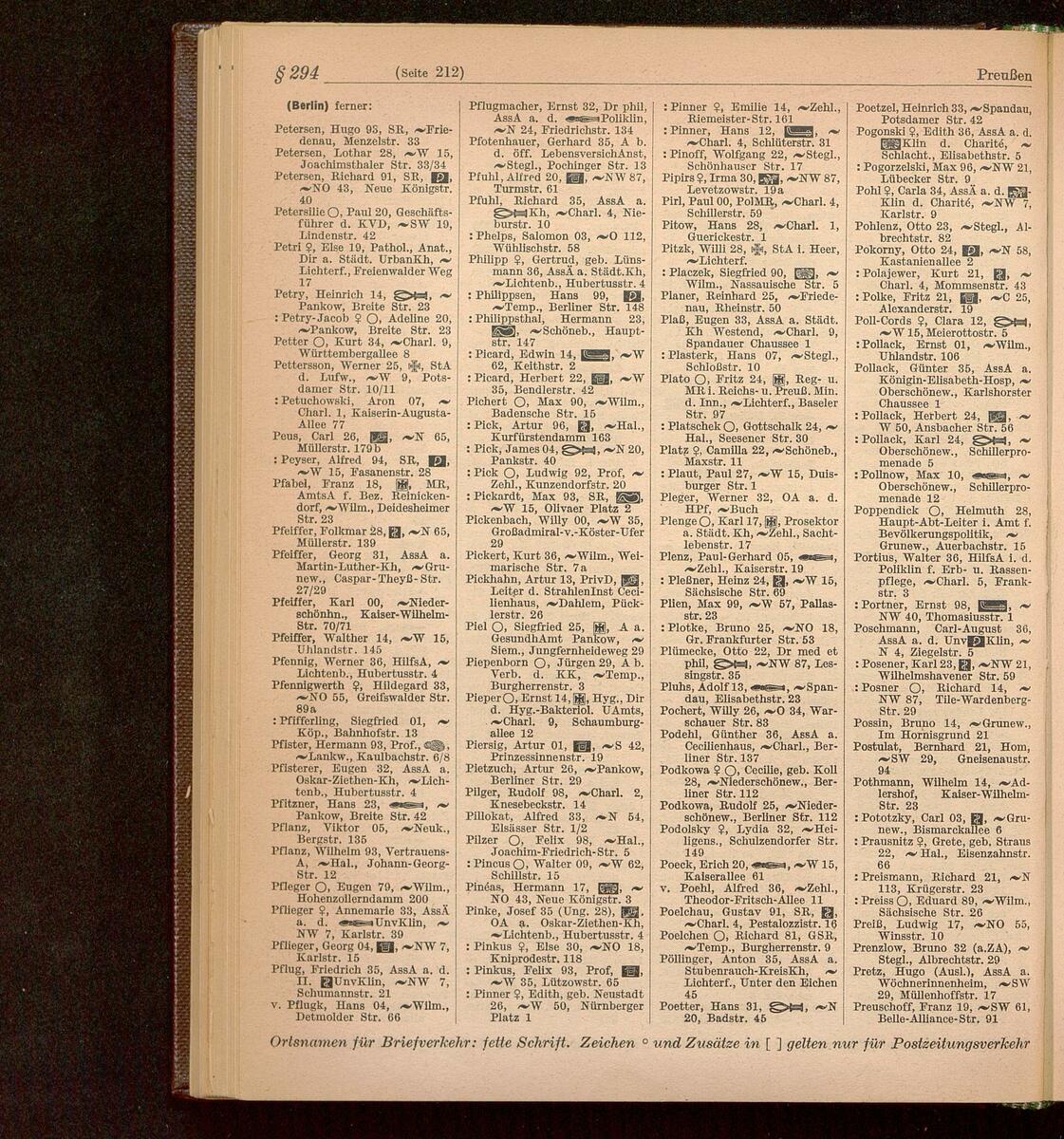

Below is a page from a German commercial

address book (the equivalent of North America’s “yellow pages”), in this

case listing physicians in Prussia. Several of the doctors (at least

half) have been singled out with a colon in front of their names, which

indicated that they were Jewish. Over course of the 1930s, Jews had

already been slowly expelled from the professions through more direct

measures, from prohibitions against employment in the civil service to

restrictions on medical school admissions, among other regulations. This

list of doctors from 1937 conveyed a quiet, yet strong message: that

Germans had a choice when it came to physicians, and that in choosing,

they ought to support the values and ideals of the Nazi movement. Thus,

the list attests not only to the insidious nature of National Socialist

ideology, but also to the less easily definable cultural racism in which

Germans engaged on a daily basis.