Abstract

Banking underwent important structural development in early modern

Germany. In the process, successful moneylenders and moneychangers were

transformed into private bankers. Inflation and financial crisis,

accompanied by widespread coinage fraud at the outset of the Thirty

Years War – the so-called Kipper und

Wipperzeit (1619-23) – provided further incentive to establish

trustworthy banking facilities. Private banks were built upon the assets

and reputations of their owners, whereas public lending sources were

tied to government and municipal bonds and mortgages on landed property.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, private bankers were

reluctant to risk financing the costly activities of absolutist states,

which sometimes (in Prussia, notably) were self-funded ventures.

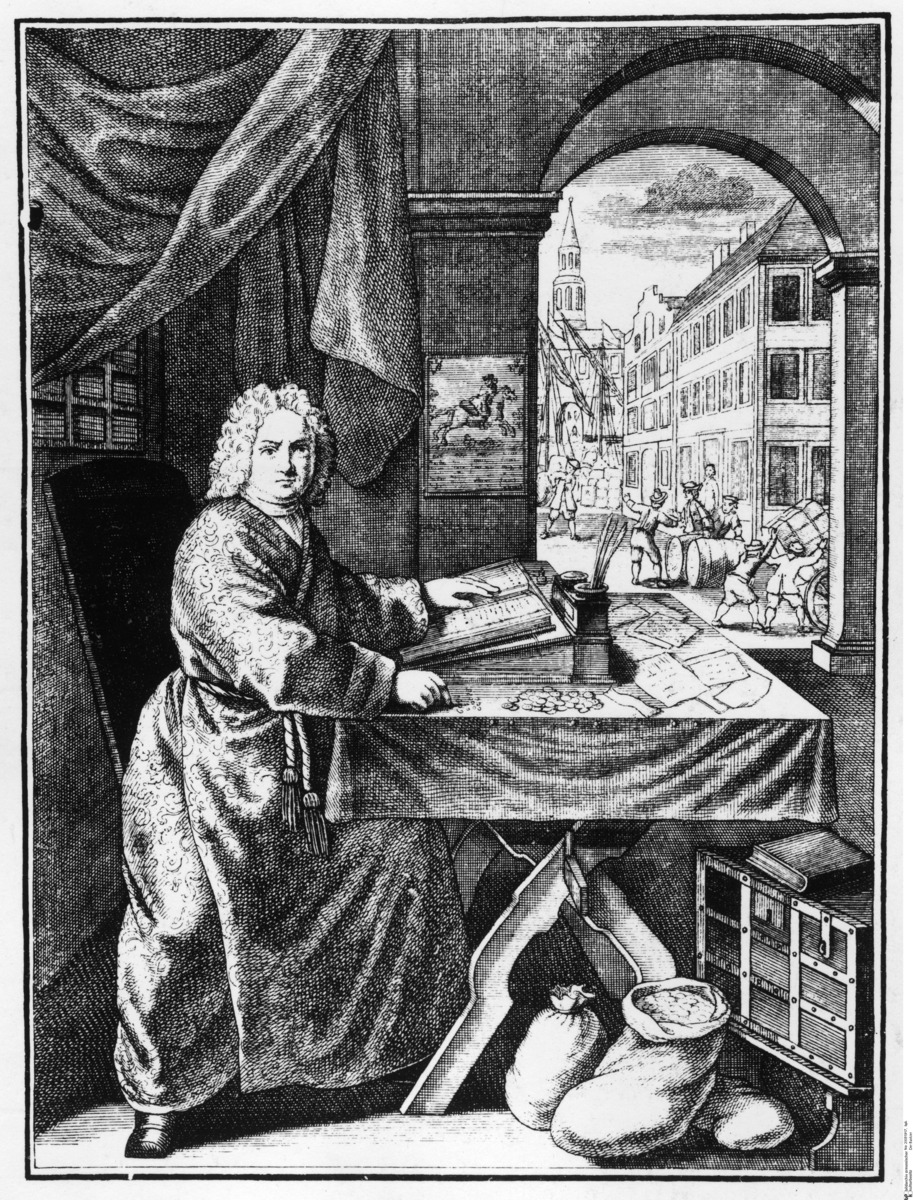

The banker depicted in this engraving confidently inventories his

cash deposits. The papers spread on the table are, presumably,

profit-bearing bills of exchange, a financial instrument used in Europe

since the Middle Ages. The view through the window shows the hustle and

bustle of commercial activity on the urban streets outside.