Source

Frau W. from East Berlin to Christiane M. in Elmshorn (West Germany) on May 10, 1980

Writer: Family W.

Recipient: Christiane M.

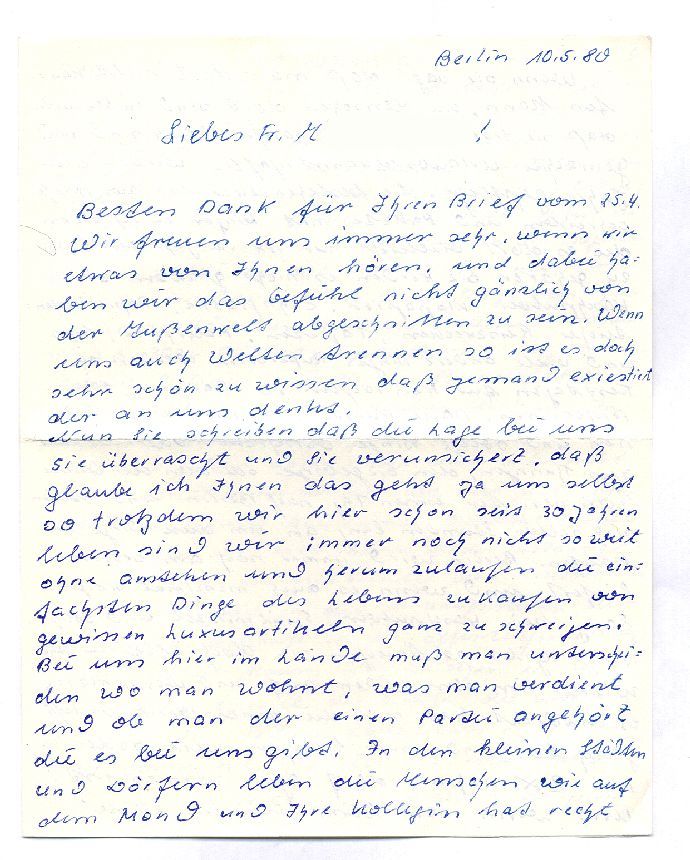

Berlin, May 10, 1980

Dear Miss M.!

Many thanks for your letter of April 25th. We’re always very happy to hear from you, and when we do, we have the feeling that we’re not completely cut off from the outside world. Even if we’re separated by worlds, it’s still nice to know that someone is thinking of us.

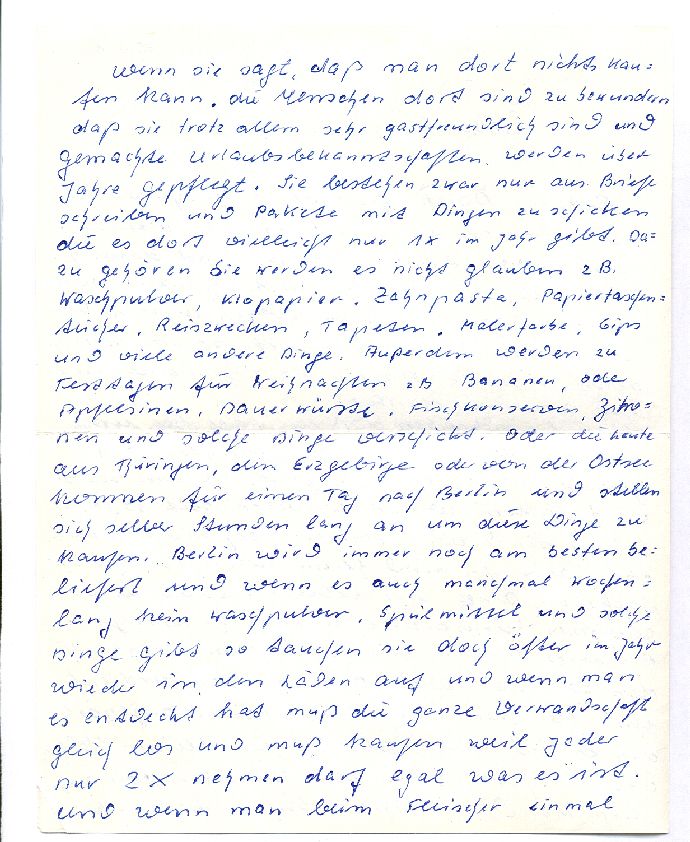

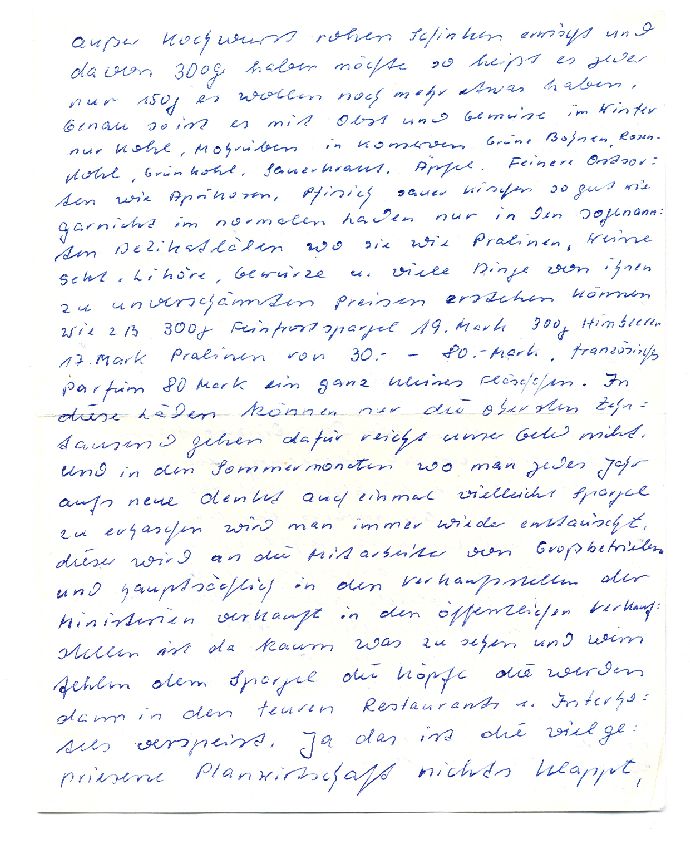

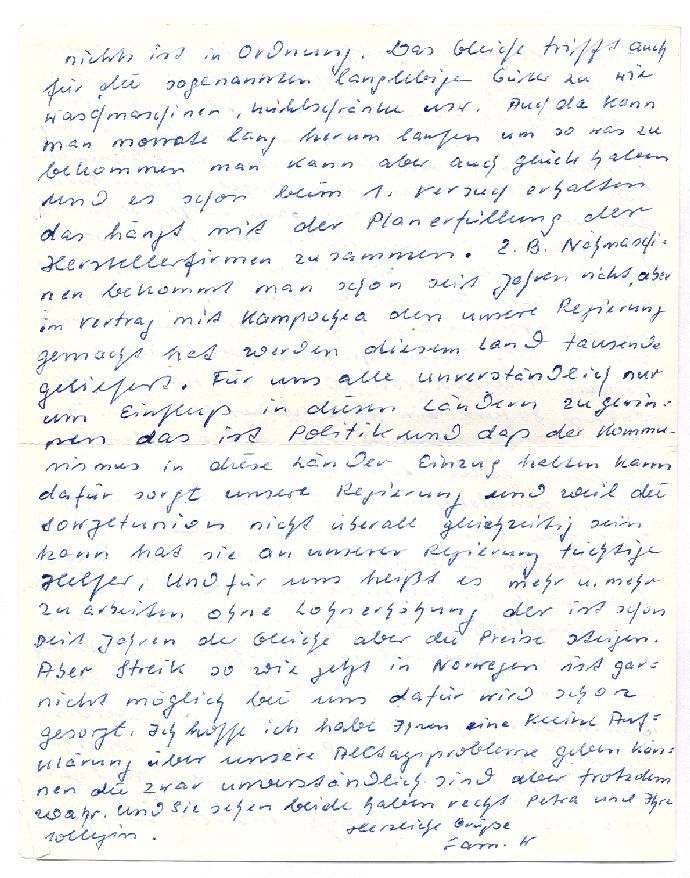

Now, you write that our situation here surprises and unsettles you. I believe you, we feel much the same way; even though we’ve been living here for thirty years, we’re still not at the point where we don’t have to stand in line and run around to purchase the most basic things in life, to say nothing of certain luxury items. Here in our country, the situation varies according to where you live, what you earn, and whether you belong to the one party that exists. In the small cities and villages, the people live like they’re on the moon – and your colleague is right when she says that you can’t buy anything there. I admire those people for being very hospitable in spite of it all; the friendships they make during vacations are maintained for years. To be sure, they consist only of letters and sending packages with things that you can only get there maybe once a year. Those include, for example, you won’t believe it, powder laundry detergent, toilet paper, toothpaste, tissues, thumbtacks, wallpaper, wall paint, plaster, and many other things. Moreover, for the Christmas holidays, for example, people send bananas, or oranges, smoked sausage, canned fish, lemons, and the like. Or the people from Thuringia, the Ore Mountains, or the Baltic Sea come to Berlin for a day and stand in line for hours in order to buy these things. Berlin still has the best inventory levels, and even if, sometimes, there is no laundry detergent, dish soap, and the like, these things do reappear in the stores more frequently throughout the year, and if you find something, all your relatives have to go out right away and buy it, because each person is limited to two items, no matter what it is. And if you happen to come across raw ham at the butcher’s, aside from the usual cooked sausage, and you’d like to have 300 grams, you’re told that each person is limited to 150 grams – after all, others want some too. It’s the same with fruit and vegetables in the winter, only cabbage, canned carrots, green beans, brussels sprouts, green cabbage, sauerkraut, apples. The finer kinds of fruit, like apricots, peaches, and tart cherries, are virtually nonexistent in regular stores; they are only to be had in the so-called Delikatläden [specialty shops for luxury items], where you can purchase pralines, wine, champagne, liquors, spices, and lots of things at outrageous prices. For example, 300 grams of top-grade asparagus costs 19 Marks, 300 grams of raspberries costs 17 Marks, pralines cost 30-80 Marks, French perfume is 80 Marks for a very small bottle. Only the top ten thousand [richest people] can go to these shops, our money doesn’t go far enough. And in the summer months, when you think, year after year, that for once you just might get your hands on some asparagus, you’re disappointed time and again: it’s sold to workers in large enterprises and chiefly in stores for the government ministries; you’ll hardly see anything in public stores, and if you do, then the tips will be missing (those are served in the expensive restaurants and Interhotels). Yes, that’s the highly vaunted planned economy, nothing works, nothing is in order. The same applies to so-called durable goods like washing machines, refrigerators, and so on. Here, too, you can run around for months to get something of this sort, but you can also get lucky and get one on the first try – it all depends on the fulfillment of the plan by the manufacturers. For example, sewing machines have been unavailable [here] for years now, but under the agreement that our government signed with Kampuchea [now Cambodia], thousands are being delivered to that country. It’s incomprehensible to all of us that they’re doing this just to gain influence in those [communist] countries; that’s politics, and our government makes sure that communism can take root in those countries, and because the Soviet Union cannot be everywhere at once, it has capable helpers in our government. And for us that means working more and more without a wage increase; it’s been the same for years, but the prices are still rising. Yet a strike like the one in Norway is in no way possible here – they make sure of that. I hope that I’ve been able to give you a little insight into our everyday problems, which are incomprehensible but nevertheless true. And you see that both are right, Petra and your colleague.

Warm regards,

Fam. W.

Source: Frau W. from East Berlin to Christine M. in Elmshorn, May 10, 1980; Briefsammlung, Museumsstiftung Post und Telekommunikation. Republished with permission. Available online at: https://www.briefsammlung.de/post-von-drueben/brief.html?action=detail&what=letter&id=1456&le_keyword=Briefmarken