Source

Related text

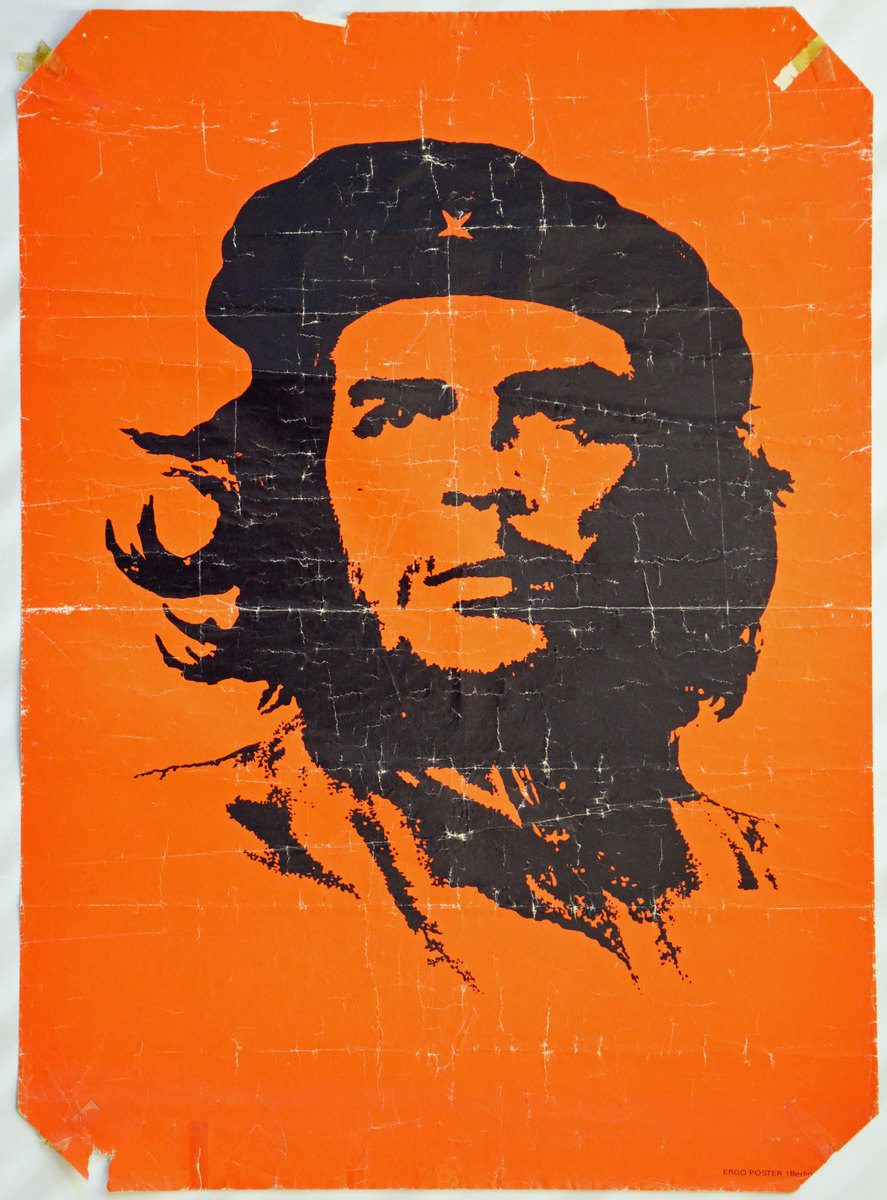

A German website called “Mythos Che” (1997–2000) attests to Che Guevara’s enduring hold on the popular imagination. An essay from that site provides background information on the iconic photograph that propagated the myth of Che around the world. Unfortunately, it was impossible to determine authorship of the essay or to verify other details of publication. Still portions of it have been reproduced below in the interest of sparking discussion.

Would the myth (of Che) be as powerful without this image? Would it have spread universally without this picture?

The Cuban Revolution was just a year old when the French freighter “La Coubre” was blown up in the port of Havana. [ . . . ]. The blast wave, flying wreckage from the cargo ship, and metal fragments killed 136 people. Sabotage was suspected.

During the memorial service, Alberto Diaz (called Korda), the chief photographer of the paper Revolución, had a lot of time on his hands: Fidel Castro spoke, for hours. Panning the stage, Korda ended up with Che Guevara in his viewfinder. As he tells it, he pushed the shutter button “instinctively,” because this “expression of anger and determination” on the face of the Cuban-Argentinian had “gotten under his skin.” The 1960 photograph shows the revolutionary hero in partial profile, with a buttoned-up uniform jacket, a beret with a red commander’s star, and long hair blowing slightly in the wind.

Using a retouching brush, Korda edited out a nearby rally participant and a palm branch. The photo editor of Revolución liked the photo, and he hung it on the wall in his studio. That’s where the Italian publisher Giacomo Feltrinelli saw it years later, in 1967. Since he carried with him a letter from the government, in which a high-ranking politician identified Feltrinelli as a friend of the revolution, Korda gave him two copies. [ . . . ]

Back in Europe, news of Che’s death was circulating just then, there and around the world; the Italian had posters printed, at first a few thousand, then tens and hundreds of thousands. Eventually, the image circulated around the world in the millions, on flyers and record sleeves. [ . . . ] What also circulated around the world was the myth of the selfless, passionate revolutionary who fearlessly challenged local despots and the almighty “Yankee imperialism,” who fought for the poor, for bread and schools, for human dignity and justice, who promised to launch [ . . . ] a socialist world revolution with its starting point in the South, the Third World of the have-nots. [ . . . ]

Source: http://guevara-che.angelfire.com/mythos.htm

Translation: Thomas Dunlap

Source: Poster with image of Che Guevara. Berlin (West). Date: 1970–1989. Deutsches Historisches Museum, Inv.-Nr. P 2015/85. Available online at: https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/item/R2SPXFM7H6UQUODVHJROYITJQO4UC3BO