Abstract

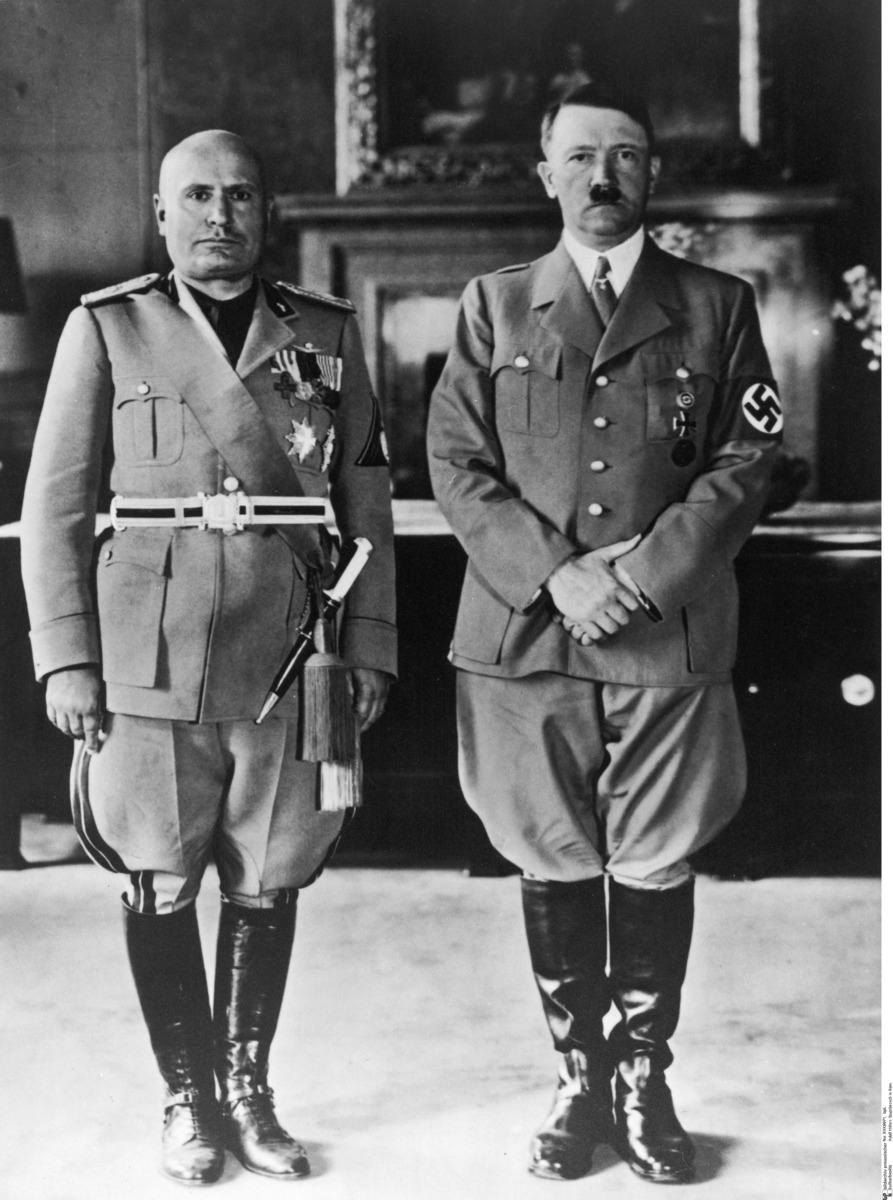

Since the 1920s, Hitler had greatly admired Italian dictator Benito

Mussolini both personally and politically, and he considered Fascist

Italy a natural ally for the German Reich. At first, however, Mussolini

was hostile to the Nazi regime. He had no sympathy for Nazi racial

theories and mistrusted Hitler’s expansionist intentions, especially

with regard to Austria and South Tyrol, which had belonged to Italy

since 1919. Up until 1935, Mussolini repeatedly protested both German

rearmament and the country’s aggressive foreign policy, and rejected all

of Hitler’s attempts at diplomatic rapprochement. The German-Italian

relationship first changed with the Italian attack on Abyssinia in

October 1935, after which the League of Nations imposed economic

sanctions on Italy and isolated the country diplomatically. By remaining

neutral in this matter, Hitler secured Mussolini’s gratitude and laid

the foundations for the later “Berlin-Rome Axis.” Their common

intervention on behalf of Franco in the Spanish Civil War put the final

seal on Mussolini’s decision to ally himself with Hitler against the

Western powers. In 1937, Italy left the League of Nations and joined the

German-Japanese “Anti-Comintern Pact.” The German-Italian rapprochement

reached its highpoint with the signing of the “Pact of Steel” on May 22,

1939, in which both sides committed themselves to mutual military and

economic support in the event of a war of aggression.