Abstract

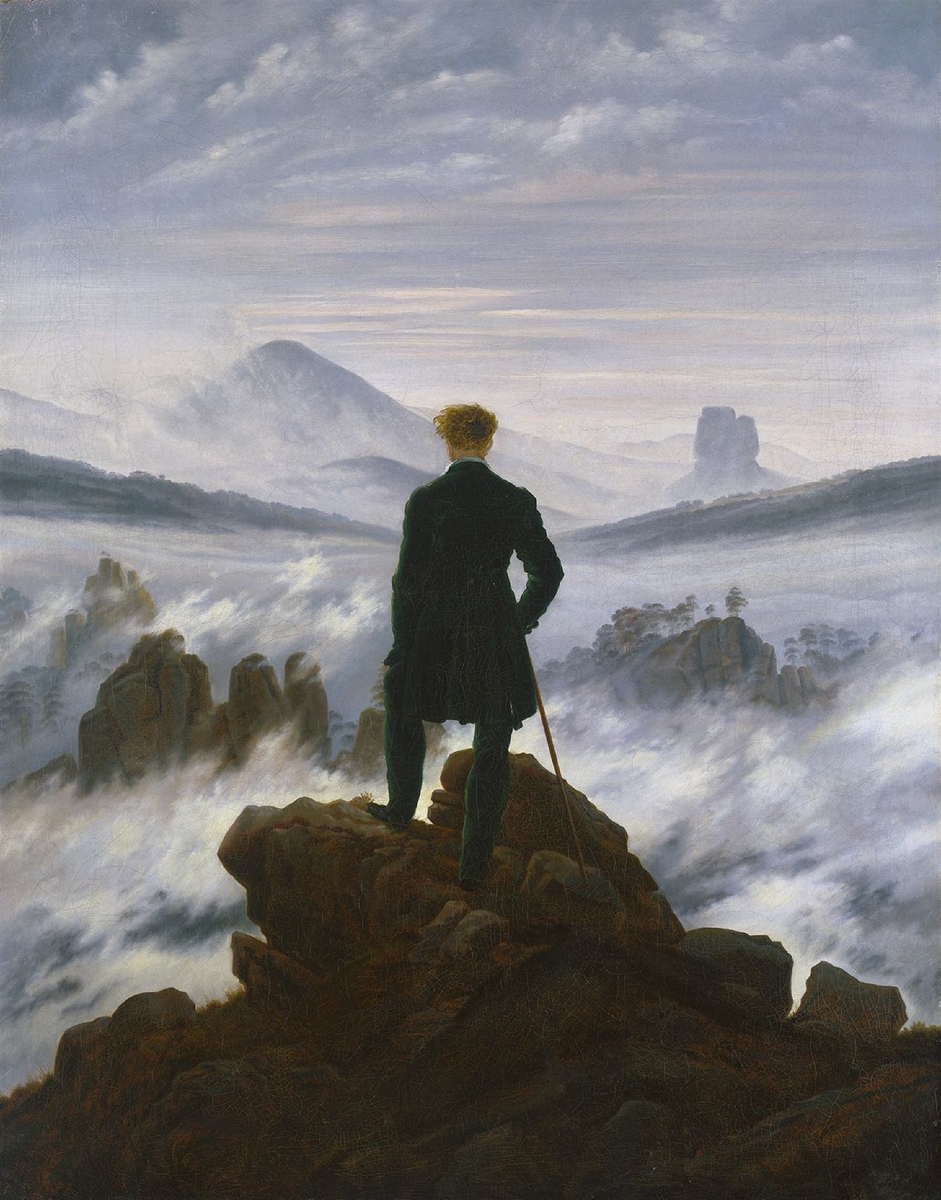

There is probably no other image in the history of art that has graced more dust jackets of books on the history, philosophy, and literature of modernity. Like Eugène Delacroix’s painting July 28: Liberty Leading the People (1830), Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above a Sea of Fog has come to represent the feeling of an entire age. This wanderer is the very embodiment of the Kantian subject, in whose perception all aesthetic judgment is born. His gaze gives meaning to the world, and yet this world remains an unknowable mystery to him, shrouded in fog. He is like Schubert’s wanderer, a stranger in the world, the very icon of modern alienation. But he is also like the traveler of English Romantic poetry, alive to the sublime glories of nature that open up before him during his pensive walks. Friedrich’s frequent use of the so-called Rückenfigur—a prominently placed figure shown entirely from the back—is a powerful commentary on the Romantic experience of art and nature. The world can only be glimpsed, experienced, and reproduced from a single point of view, in fragments, never as complete and whole in and of itself. The wanderer, like many narrators in Romantic fiction, is at once a conduit through which the reader or viewer enters the representation and, as an inscrutable other, a gatekeeper of that subjective representation’s alterity, which can never be completely shared. Friedrich’s remarkable understanding of incompleteness as a central generative force in Romantic art gives his work its aura of contemporary relevance even in the postmodern age. The complexity of his vision is especially evident in contrast to the archaic tendencies of the Nazarenes, who experienced the incompleteness of the subject entirely as a loss, which they attempted in vain to overcome with anachronistic techniques and subject matter.